The Never-Ending Phishing Scam: When “Natalie Hamilton” Reemerged with a Vengeance (and Power Drill)

Editorial and additional commentary by Tricia Howard

Executive summary

Akamai researchers have been tracking a scam campaign that has been active since at least March 2022 and has remained active through various sophisticated obfuscation techniques.

The scam’s back-end infrastructure has remained resilient, despite the fact that the scam landing pages have been taken down. There have been millions of visitors maliciously rerouted through this infrastructure.

Our analysis of a single routing site traffic paints a picture of how lucrative these scams are for attackers: They rake in an estimated US$5000 to US$150,000 (at least) annually per malicious domain.

This ongoing research led to the discovery of multiple templated sites used as front-ends for the scam infrastructure that have been tied to more than 40,000 malicious routing domains. At one point, there were 13,000 sites active concurrently, hosted on more than 20 different hosting providers.

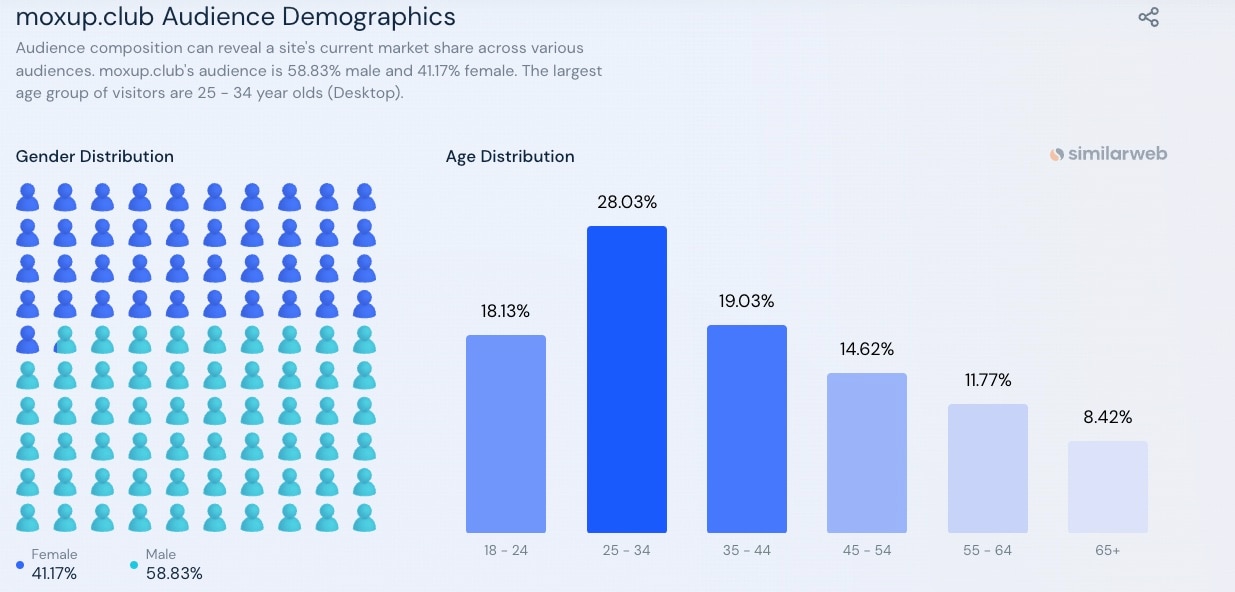

Via analysis of traffic to the scam infrastructure we can see that 58% of the potential victims are male, and 28% are in the age range of 25 to 34 years.

This infrastructure showcases the level of effort and sophistication the attackers will achieve to maintain the infrastructure behind the scam sites. It also highlights the gap between attackers and defensive products and services. Defense focuses primarily on detections and takedowns, while adversaries acknowledge that the detection of the scam is unavoidable and create obfuscations to evade this reality.

Recap

In November 2022, we published a blog post that highlighted a sophisticated phishing scam that preyed on online shoppers’ holiday sentiment. The phishing campaign began with an email that appeared to be from a legitimate retailer, offered the chance to win a prize, and used holiday spirit to engage potential victims.

The phishing campaign was notable for its use of an infrastructure that included various evasive techniques to avoid detection, including the use of URL shorteners, fake LinkedIn profiles, and legitimate web service providers to host scam redirection functionality to conceal the scam’s malicious URLs.

The attackers also used the URL fragment identifier redirection, which is a technique that uses an HTML anchor to point a browser to a specific spot in a page or website to evade detection by security products. The attackers generate randomly generated URLs to filter out unwanted visitors, and they use the power of content delivery networks (CDNs) to quickly and easily rotate phishing website domain names and IP addresses without taking down the phishing website infrastructure.

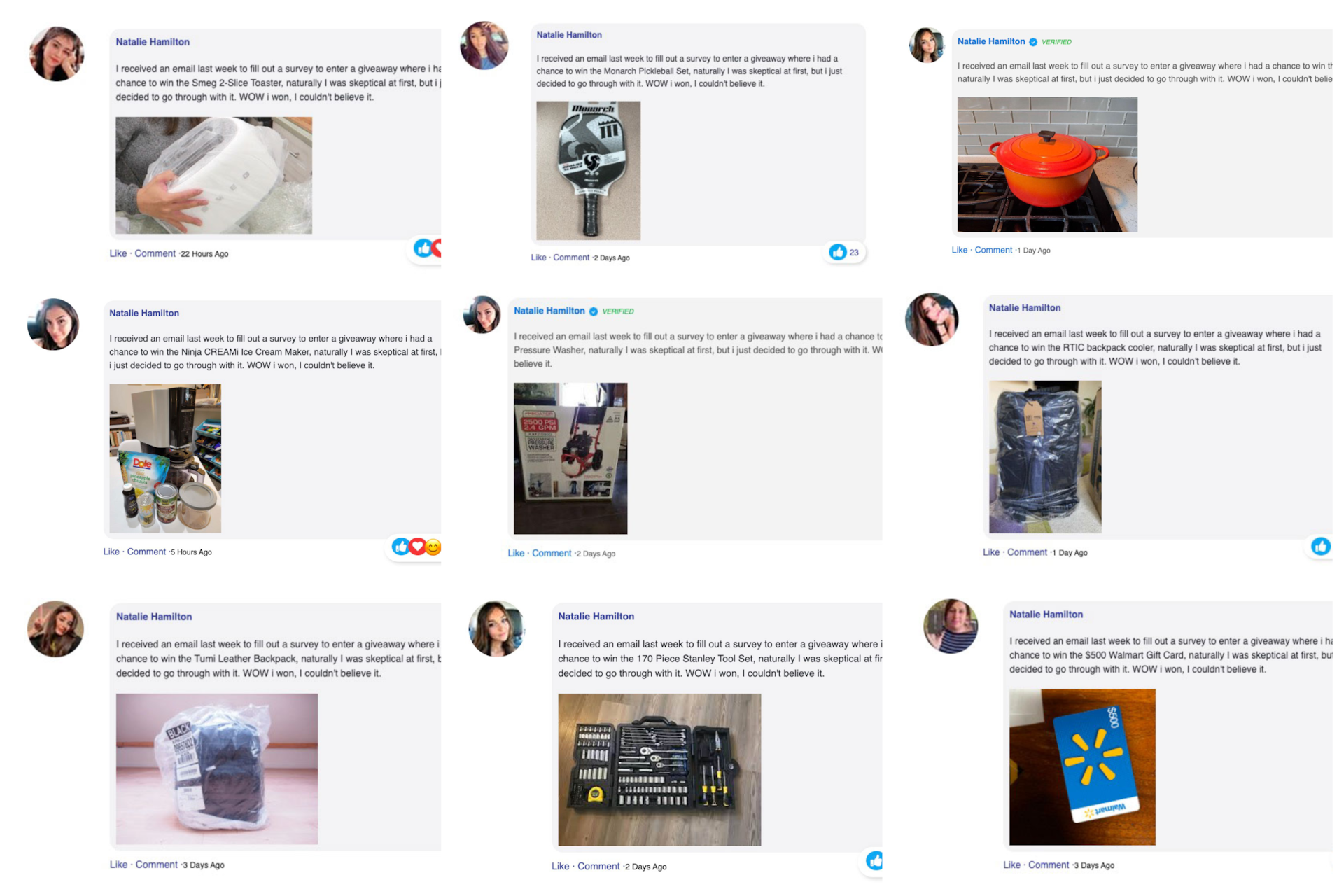

On the social engineering side of things, we saw fake users on scam websites with “testimonies” of their winning a prize. One of those fake users who caught our attention was “Natalie Hamilton”: the woman with many faces. Natalie triggered the second part of our research, described in this post, leading us to a better understanding of the outstanding scam infrastructure and the potential revenue that drives a scam that involves tens of thousands of websites and an estimated millions of victims.

Natalie Hamilton wins again

A few months after our previous blog post, as we continued to track those scam campaigns, we came across Natalie Hamilton again — and this time she reemerged with vengeance, offering us the chance to win a power drill. Refreshing the scam website users’ testimonials multiple times resulted in the same text but with a different profile image and power drill photo (Figure 1).

The fact that Natalie came back and this scam continues to thrive motivated us to look further into the operation and infrastructure behind No Good Natalie.

Whack-a-Mole — resilience and persistence of an infrastructure

By looking into redirecting components of the scam, we were able to see scam infrastructure that contains a chain of redirections, with anti-detection features, leading to the ability of the infrastructure to remain resilient even after parts of the infrastructure are being disabled. Evidence of the infrastructure’s resilience was seen in initial redirecting links, found in the wild, known to be leading to the scam landing website. Ten months after their initial use, even after the original landing website was taken down, the links are still active and leading to new phishing websites, like the well-known game Whack-a-Mole.

That is, even after the original phishing landing website was taken down and was no longer active, the redirecting infrastructure was still active, enabling the redirection to a new scam website.

Furthermore, as we monitored the routing component (Figure 2), we were able to recognize the routing of the infrastructure as evidence for persistence of the scam. The domain that facilitates the routing component shows that this domain has been used for redirecting victims to malicious landing websites since at least since March 2022, with evidence of redirecting to at least 30 different malicious domains.

By looking at all 30 landing websites on VirusTotal, we can see that these websites are flagged as malicious by an average of 9.5 detection engines; at the other end, the routing domain has weak detection signal with single detection engine. The registration of the routing domain was done in May 2021, and the domain ceased to exist in April 2023.

Revealing insights on potential victims

Since that routing domain was active for a long period and had massive amounts of potential victims redirected through it, the website became popular enough to be ranked by Similarweb, a web-ranking platform. A granular look at this traffic offers us a rare glimpse into just how successful these scams are.

Because these domains are owned by adversaries, the level of detail shown by Similarweb is unique. We were able to see insights such as the number of visitors (potential victims) and the demographics of those visitors, and much more. Analyzing these characteristics can provide data points to create an estimation of the revenue stream that this kind of infrastructure can yield to adversaries.

We saw between 50,000 to 120,000 visits per month since the domain was initially ranked (Figure 3). This information is another testimony for the persistence of this routing component in the scam infrastructure. Moreover, it shows the number of victims being redirected on different attack campaigns and that number is evidence of the scam’s magnitude.

The persistent and continuous stream of visitors (also known as the number of potential victims) can help us understand the economy behind these kinds of scams. This evidence can explain adversary motivation — and why phishing scams are still thriving and are apparently here to stay.

A lucrative haul

Based on information seen on Similarweb, we can assume approximately 1 million visitors were redirected through the routing component domain. Even if only 0.1% of those visitors give away their credentials, that equals 1,000 stolen credentials. Stolen credentials on dark markets sell for between US$5 and US$150 each — for a potential haul of US$5,000 to US$150,000 a year. Factoring in this level of potential revenue easily explains what drives adversary motivation to commit scams and fraud activity.

Demographics data

Another interesting insight can be seen in the demographics data (Figure 4). According to Similarweb, 28% of the potential victims were between the ages 25 and 34 years, and 58% of the total potential victims were male. This kind of information is valuable when designing phishing awareness program focus groups.

“Aria — conversion optimization tactics”

As we collect evidence that shows the routing domain’s persistence, it is hard not to wonder how this domain has both remained active and avoided being flagged as malicious.

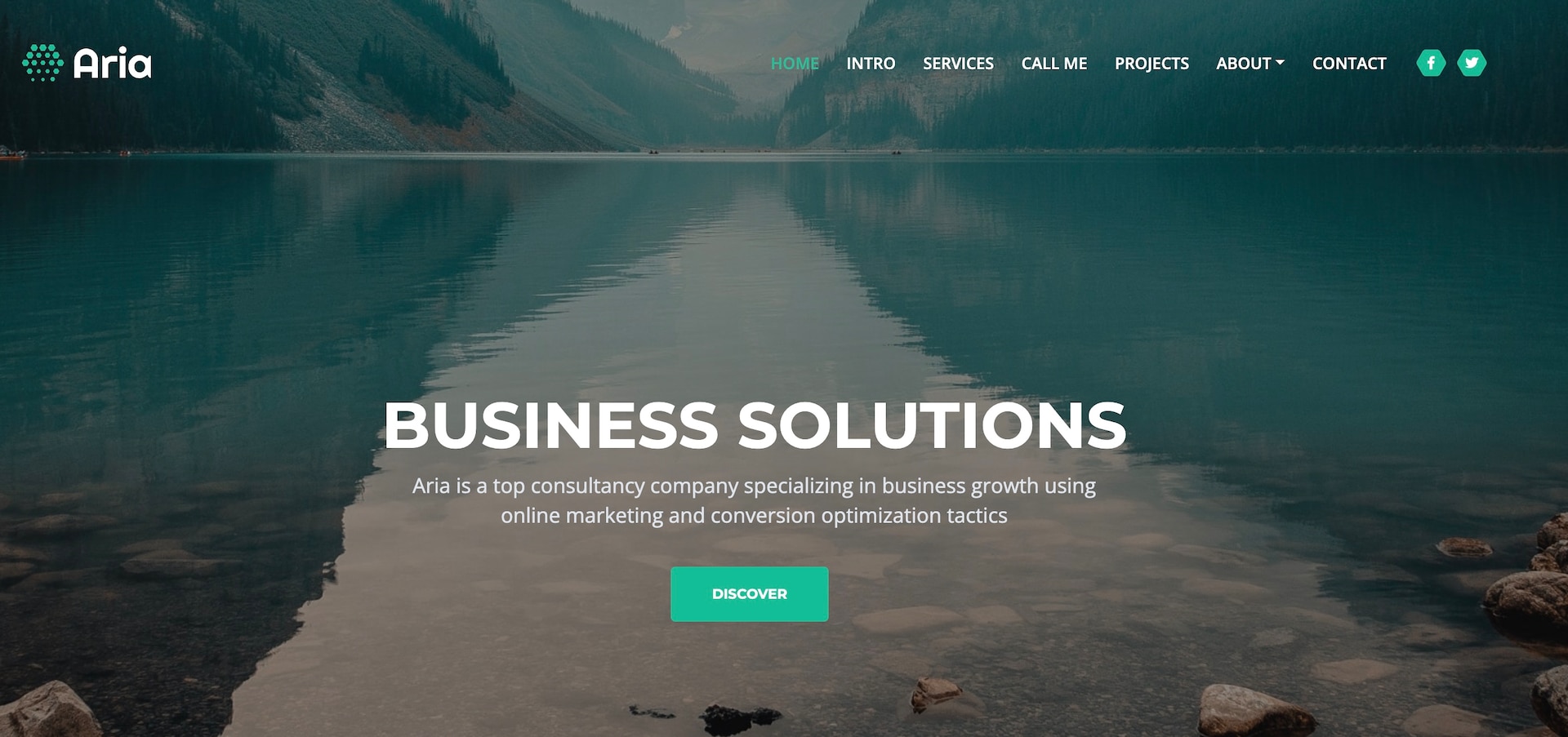

To answer this, we decided to further analyze the routing domain to better understand the persistent nature of this scam infrastructure. Although we know that back-end functionality enables redirection and filtering, the front end revealed a domain that appears to be a marketing company named Aria, which according to the website offers “online marketing and conversion optimization tactics” (Figure 5).

“Hello, my name is [fill in the blank]”

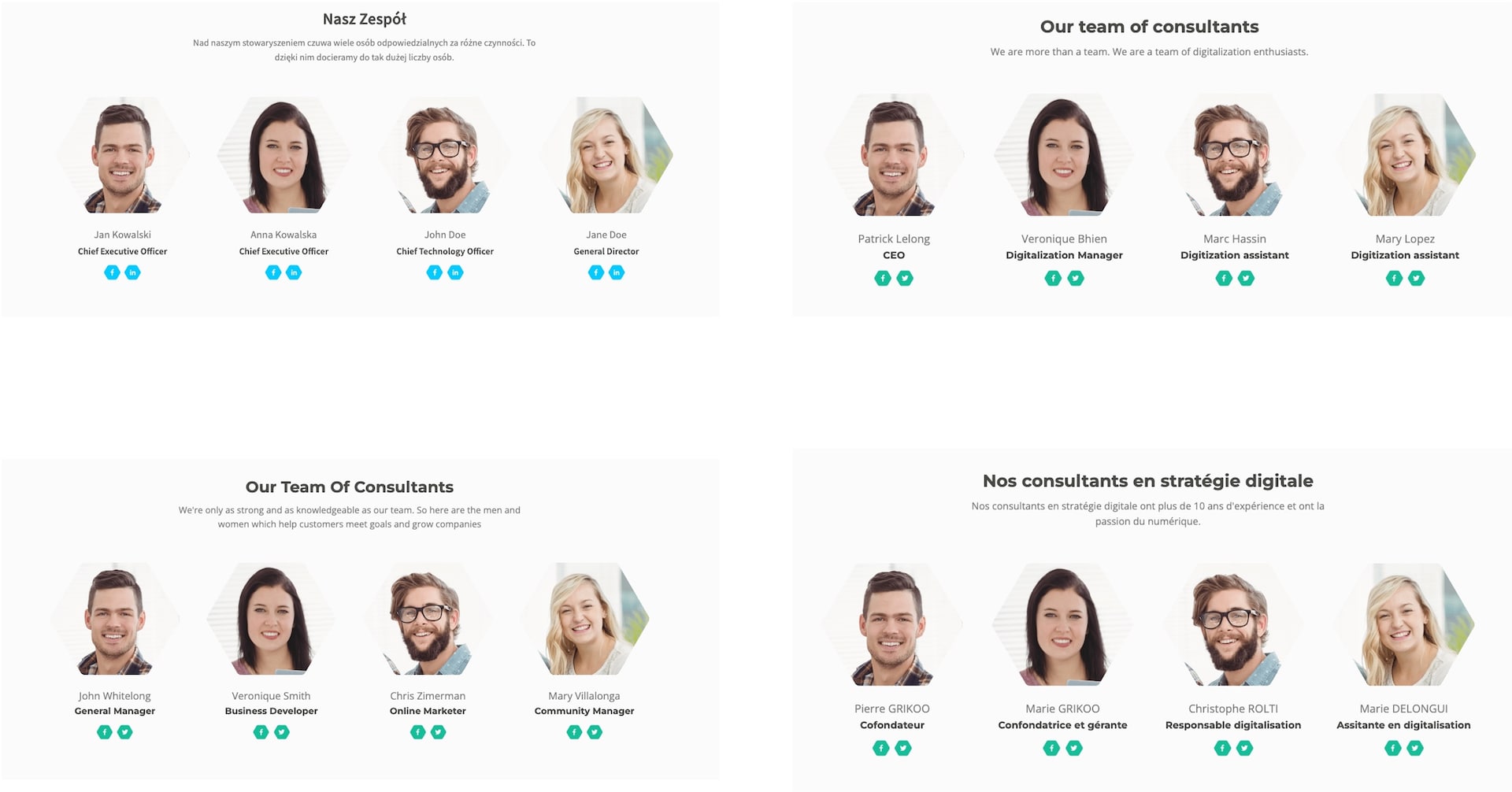

Examination of that website content revealed that it is not a real website nor real company — it is a templated website being reused in the wild. Evidence for that can be seen in the employees’ profiles on the website; the same photos are being used on different websites across the internet, each with a different name, language, and role (Figure 6).

We also found 10,954 domains that were active at some point that used the same front-end Aria ruse. Moreover, verifying those domains with the back-end redirecting and routing functionality shows that 1,973 are still active websites being hosted on more than 20 different hosting providers, meaning these websites are part of a much larger scam infrastructure.

A search for some indicators of compromise on those routing and redirecting domains uncovers evidence indicating that some of these domains were used to redirect different scam and phishing campaigns, and yet again the routing domains were not flagged as malicious by platforms like VirusTotal.

Some of those redirecting domains also saw a lot of traffic and, as a result, became ranked by Similarweb, highlighting the scale and the potential financial gain by the adversary. If a single routing domain was estimated for a revenue stream of between US$5000 to US$150,000 a year (as previously indicated), then another 1,973 active routing domains increases that potential revenue stream significantly.

“Notes — a passionate web company”

Although those findings were surprising and overwhelming, we didn’t stop there. Further research enabled us to find evidence on the existence of another, parallel and related, scam network that was operating with the same redirecting functionality.

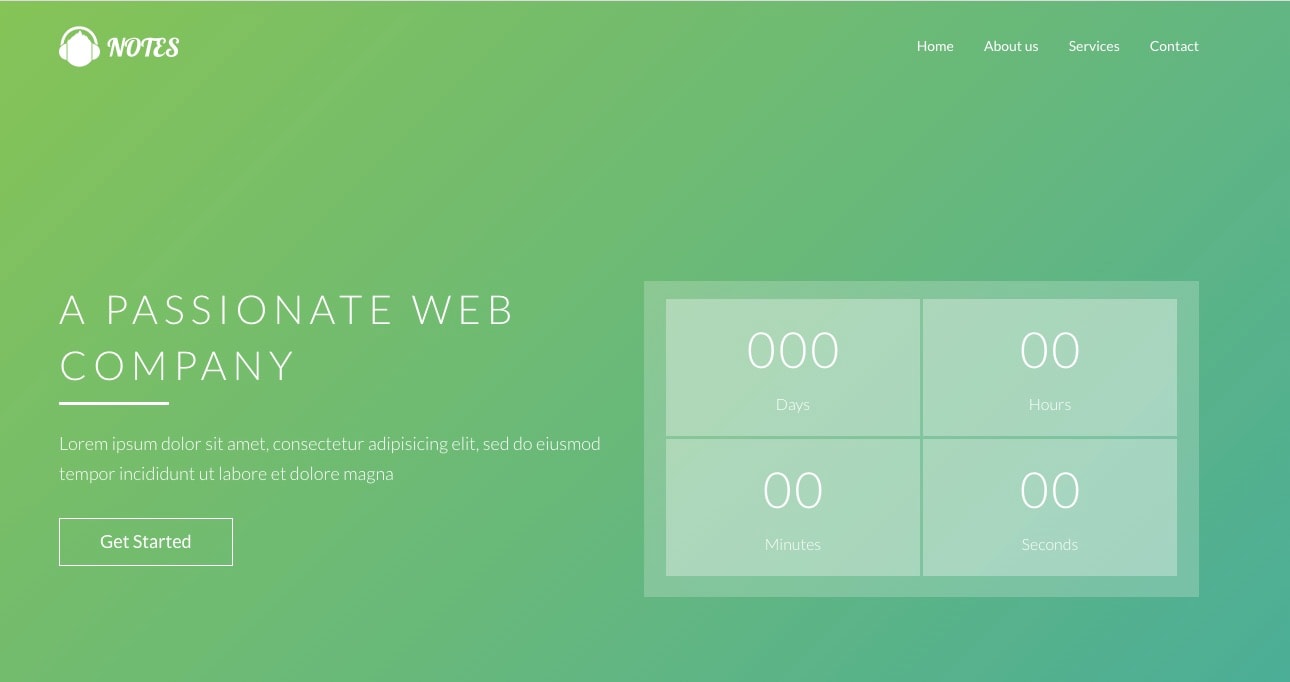

The front-end template that was used in this case was for a company named Notes, which bills itself as “A Passionate Web Company” (Figure 7). On this infrastructure we were able to see 28,776 domains that at one point in time were active with that same template. By verifying those domains with the back-end redirecting and routing functionality, we determined that 9,839 are still active websites.

We believe that the Notes scam infrastructure was created as a backup to be activated as the Aria infrastructure is disabled; over time, we started seeing more activities going through Notes.

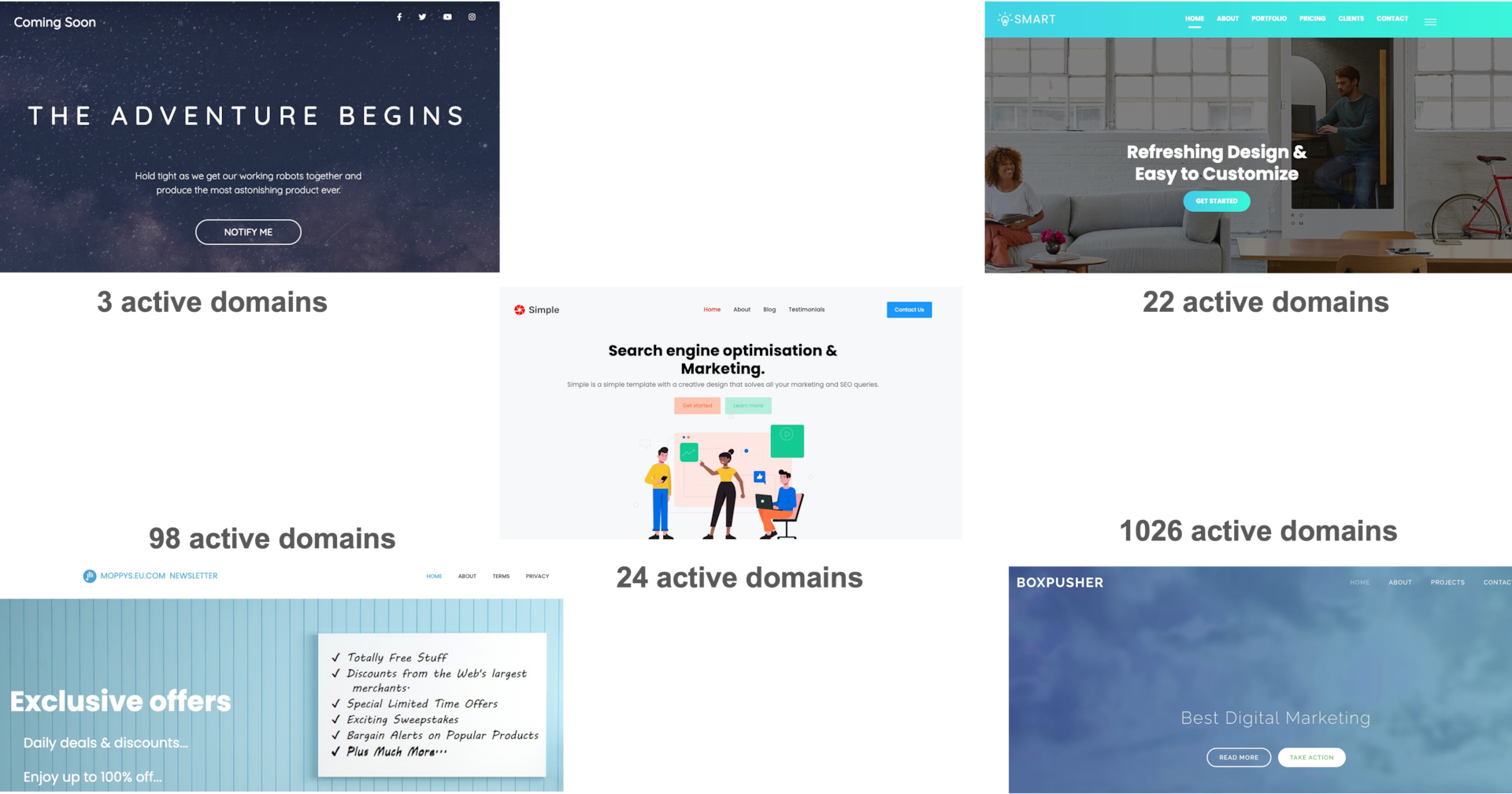

Uncovering more templates

As we continued our research, we were stunned to discover another five template websites that have a redirection functionality in the back end, with the same redirecting functionality as both the Aria and Notes templates (Figure 8). The numbers of domains associated with those new templates were less significant, yet they reveal the large scale and high level of operations involved in the scam infrastructure. The five additional templates were associated with the previously seen templates, thus we consider them to be part of the same infrastructure.

Summary

Natalie Hamilton continues to emerge in different shapes and forms. We were able to track her as a winner of many prizes in many campaigns as part of this continued scam (Figure 9). The scam’s longevity and the large number of brands it has abused indicates its depth. This scam is relevant to every company that is trying to protect their brand’s reputation.

This scam showcases the depths of the adversary’s capabilities, techniques, and scale, which yield successful results. The volume of traffic on these sites proves how effective these campaigns are. As detailed in our previous blog post, the endless set of techniques makes the detection of scams challenging for defenders: these threat actors are using techniques that can go undetected, even by security measures.

The infrastructure can filter out unwanted access and rotate landing websites (just to use two examples), which makes detections and takedowns difficult. Once we understood the complexity of the infrastructure being used — the distribution, scale, and deployment — it became clear how the scam has persisted. Moreover, our research highlights the adversary’s ecosystem, objectives, and potential profit.

Delayed detection can pay off

The analysis of this infrastructure illuminates the gaps between threat actors and defensive products and services. The adversaries have a deep understanding of how defensive forces operate, and thus include measures to evade detection and mitigation in their phishing scams. In most cases, defensive products and services focus on detections and takedowns, while adversaries acknowledge that the detection of the scam is unavoidable. Therefore, they use a variety of evasive techniques to delay detection. The longer they stay under the detection radar, the more money they will make.

This scam thrives in the gray area of cyberspace. Although other threats such as malware, supply chain, and ransomware attacks get the attention, scam and phishing attacks are often overlooked and dismissed with arguments of lack of resources and priority. The threat landscape is overwhelming, the level of sophistication displayed in this infrastructure shows exactly that.

The line between legit and scam

The routing and redirecting infrastructure presented in this research is also evidence for the blurring line between what is considered legit and what is a scam. The infrastructure is not hosting malicious content — it just enables the delivery of the content — therefore, incriminating the infrastructure for takedown is much more challenging.

Adversaries raise the bar. We need to revise the way we detect and take down malicious content, increase brand motivation to fight back against scams, detect landing websites and malicious infrastructure more quickly, work together with hosting services to reduce the time for takedowns, and more. It is the time for us to step up our game, as well.

Stay vigilant

The Akamai Security Intelligence Group will continue to monitor this scam, as well as others like it, and provide these posts. It is imperative that security professionals and consumers alike be wary of these scams as they have real-world consequences. To stay up to date with breaking security research, follow us on Twitter!