Data Center Ransomware

This is the first in a series of posts about ransomware, dealing with ransomware history, technological developments and Guardicore forecast for future trends.

Ransomware is malware that infects your computer systems and restricts access to it, until a ransom is paid. Once your computer is infected, the malware hijacks your files, locks them up with virtually unbreakable encryption and demands a ransom of up to $2000 in Bitcoins to unscramble them.

Ransomware has been on the rise over the past few years, proving extremely profitable for its authors. Targeted mainly at individuals at first, the FBI’s recent announcement from June 2015 reveals that CryptoWall, the most prevalent ransomware operating today, is now targeting both individuals and businesses. In September 2014 the Australian’s ABC 24-hour news channel was knocked off the air for half an hour after it fell victim to CryptoWall.

Judging by the numbers, ransomware is here to stay. In 2010, the Russian WinLock ransomware reportedly earned its creators over $16 million. In 2013, the CryptoLocker cybercrime group’s profits estimated anywhere between $3 million and $27 million. According to the FBI report based on nearly 1000 complaints made to IC3, the CryptoWall group has extorted so far around $18 million from victims in the US alone. Based on the estimates that North America is responsible for less than a quarter of CryptoWall revenues, the CryptoWall cybercrime gang is set to earn over $100 million in the coming year.>/p>

Ransomware History

Ransomware first debuted with the “AIDS” Trojan back in 1989, infecting systems through a floppy disk. The notion of using cryptography for the sake of extortion was first described in a paper by two researchers Adam Young and Moti Yung in 1996. This is when the term cryptovirology was coined, describing the use of public-key cryptology in ransomware.

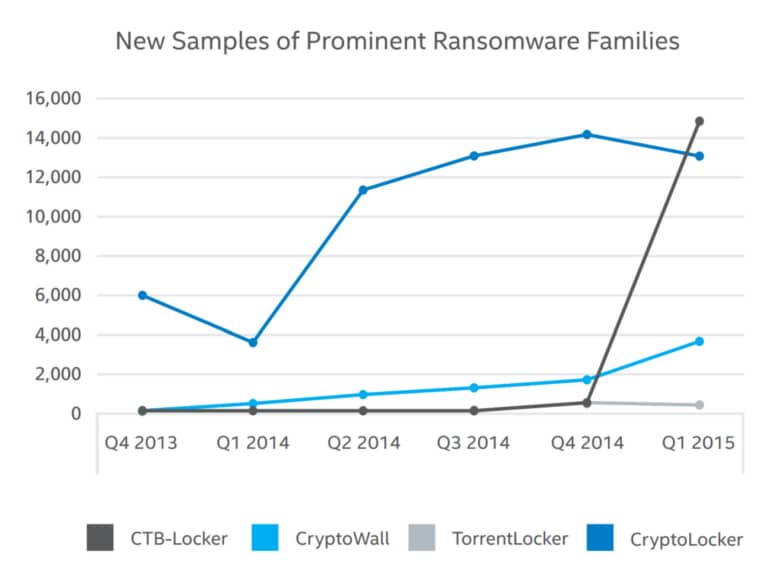

CryptoLocker, the most famous ransomware family, appeared on 2013, only to be stopped a year later as its distribution vehicle GameOver Zeus Network was taken down. Currently the top ransomware families are CryptoWall, TorrentLocker and CTB-Locker, according to McAFee Labs Threats Report from May 2015.

Over the years, ransomware has improved dramatically, becoming technologically mature:

- Advanced asymmetric encryption. Perfectly suited to encrypt data while denying victim’s ability to decrypt it, asymmetric encryption has been an integral part of ransomware since 1996. Improvements made to key size and implementations over the past years have stabilized ransomware encryption and made it next to impossible to compromise. The 2005 gpCode (or PGPCoder) ransomware, though innovative for its time, had many weaknesses (like this) allowing victims to recover data without paying. Later malware such as Archiveus, Krotten, Cryzip, MayArchive etc. were already using ever-increasing key sizes. CryptoLocker (or Crilock) that arrived in 2013 set new standards with no known encryption weaknesses.

- Encryption of network shares and cloud synchronized files. As user files are shifting to network and cloud storage, ransomware also added support for this with the introduction of CryptoLocker in 2013.

- Network attached storage (NAS) disk and rack arrays were first targeted in 2014 with Synolocker that remotely encrypted all data on the servers.

- RansomWeb. Earlier this year, a Swiss researcher reported a sophisticated attack called RansomWeb. In these attacks, databases are gradually encrypted over long periods of time, rendering backups ineffective. Throughout the attack period, the attacker operates as Man In The Middle (MITM). Once encrypted data is accessed, it is decrypted on the fly, making the victim unaware of the situation, until the attacker demands ransom.

- Bitcoin payment. The introduction of the Bitcoin as a means of payment has made ransom collection much simpler and safer for its operators. Also, the availability of the bitcoin money allows attackers to enforce shorter ultimatum periods and increase pressure on victims.

- Anti-detection techniques. Similarly to other sophisticated malware, ransomware enjoys extended periods of anti virus evasion, allowing enough time for the campaign to achieve its malicious goals. This is because of the ever-growing number of ransomware samples, which according to McAfee had almost tripled each year between 2010 and 2013. During the first quarter of 2015 samples rose by 165%, with a total of over 2 million ransomware samples known to date.

- Implementation of advanced technologies and methodologies. These techniques include embedding of zero-day vulnerabilities into ransomware exploitation kits; compromised digital signatures; executable and C&C communication disguise techniques; destruction of volume shadow copies; and exploitation of stored credentials used to infect cloud backup data.

- Geo-localized campaigns: A lot of effort is put into effective exploitation by localizing malware campaigns to match users’ web behavior patterns and preferences

Source: McAfee Labs, 2015

The Future of Ransomware

So where is ransomware going? Is it a possible scenario that ransomware campaigns will become a significant threat to enterprises, and take control over large data centers?

We believe that the answer is YES and that this is inevitable. We’ll have more on it in our next post.