DDoS Extortion Examination

In terms of the Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) landscape, 2020 was almost boring prior to the beginning of August. The excitement from the record peak Gbps and Mpps seen in early summer had worn off, and we weren't seeing a ton of interesting attacks

Things changed abruptly early in the month, as a wave of ransom letters and associated attacks targeted businesses across a number of industries, claiming to be from well-known groups with names like "Fancy Bear" and the "Armada Collective." The largest of these attacks sent over 200 Gbps of traffic at their targets.

The Akamai Security Intelligence Research Team (SIRT) published an advisory covering the initial findings on the attacks on August 17, 2020. The FBI issued a Flash advisory on August 28 with additional details of the threat. This threat is still active. Today's post is designed to highlight Akamai's internal research on the activity, and provide additional data.

Opening hand

Ransom DoS (RDoS) isn't new to Akamai or our customers. We've been dealing with this issue and these groups for as long as they've existed. This threat had been relatively quiet since November, 2019, when a group claiming to be 'Cozy Bear' had performed similar attacks. There is a definite ebb and flow to extortion DDoS attacks, but the current attacks are more distributed with regards to both the industries, and where the target companies are headquartered.

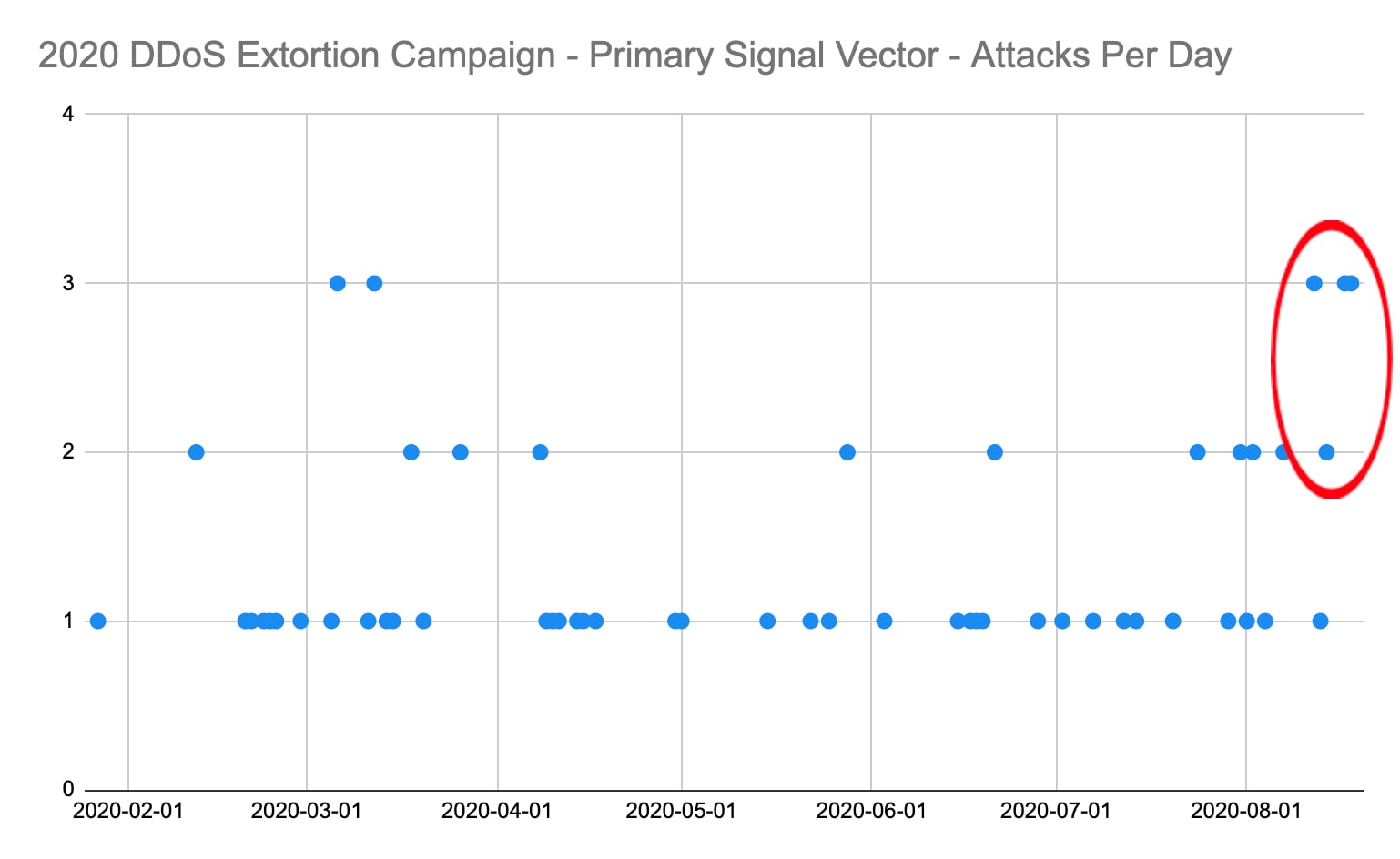

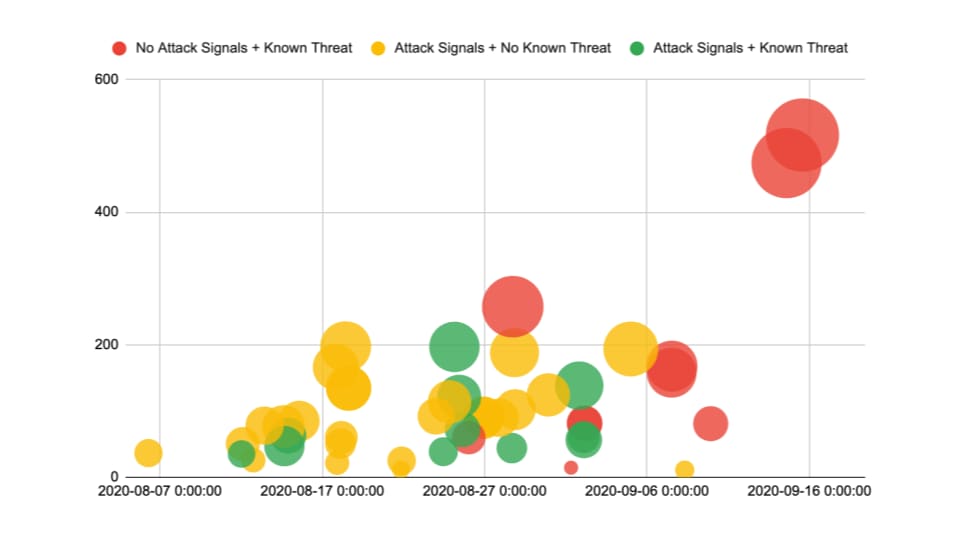

The indicators, also known as Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs,) associated with the current series of attacks include the following vectors: DNS Flood, WS-Discovery (WSD) Flood, GRE Protocol Flood, SYN Flood, and Apple Remote Management services (ARMS). An increase in the use of these vectors was unusual, as shown in Figure 1, but by themselves, they only represented a very weak signal that something new was in the works.

Fig. 1: Without supporting indicators, an increase in uncommon vectors was not enough to indicate extortion DDoS attacks

Fig. 1: Without supporting indicators, an increase in uncommon vectors was not enough to indicate extortion DDoS attacks

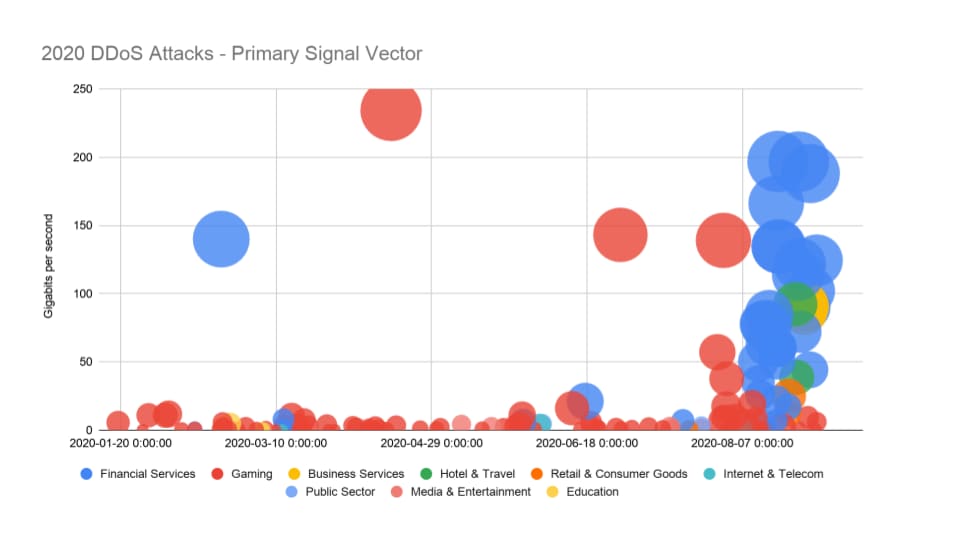

The picture started to come into focus when further inspection revealed a trend of attacks that included specific, uncommon vectors. These attacks were abnormal, because they showed both higher Bits Per Second (BPS), and Packets Per Second (PPS) than similar attacks had displayed a few weeks prior. As shown in Figure 2, this came into even sharper focus when we filtered the attacks by vertical. Prior to August, the signal vectors had been primarily used to target the gaming industry. Starting in August, these attacks abruptly swung to financial organizations, and later in the cycle, multiple other verticals.

Fig. 2: The size of each circle denotes the attack size in millions of packets per second

Fig. 2: The size of each circle denotes the attack size in millions of packets per second

It's not uncommon to identify bots and other DDoS tools based on the specific vectors they use in attacks. However, none of the vectors involved in these series of attacks were new. Most of the traffic was generated by reflectors, systems that were used to amplify traffic, but were not directly compromised by the attackers.

Early game

Seeing a common set of protocols being used as amplifiers in a DDoS campaign is, by itself, an indicator of new tools, or configurations, being used by criminals, rather than an indicator of an extortion campaign. What drew this together was rumors, and later extortion letters, claiming to be from two groups extorting their targets with threats of DDoS.

Multiple organizations received targeted emails claiming to be from criminal organizations, either Fancy Bear or the Armada Collective. Both of these names have been used extensively in previous extortion campaigns, and it is beyond Akamai's capability to determine if these are the same actors or a new organization using the names.

A significant difficulty in identifying attacks associated with this campaign was that not all attacks used the same set of vectors across their target population. As organizations began speaking up about receiving extortion emails, we were given another set of indicators to use for identification.

Many extortion DDoS campaigns start as a threat letter, and never progress beyond that point. In contrast, this campaign has seen frequent "sample" attacks that prove to the target that criminals have the capability to make life difficult. Akamai does not see all of the attacks related to the extortion campaign, and not all targets are willing to admit they've received an email from the attackers. We assume many of the extortion emails end up caught by spam filters or in the trash, despite the attackers best efforts.

Correlating known threats, e.g. an organization acknowledged receiving an extortion letter, with other indicators allowed us to start making educated guesses about which other attacks were part of the extortion DDoS campaign. These indicators needed to be tempered to reduce the false positive rates, and after experimenting, it was determined that attacks greater than 10 Gbps in volume that lasted longer than 10 minutes provided the best threshold for our needs.

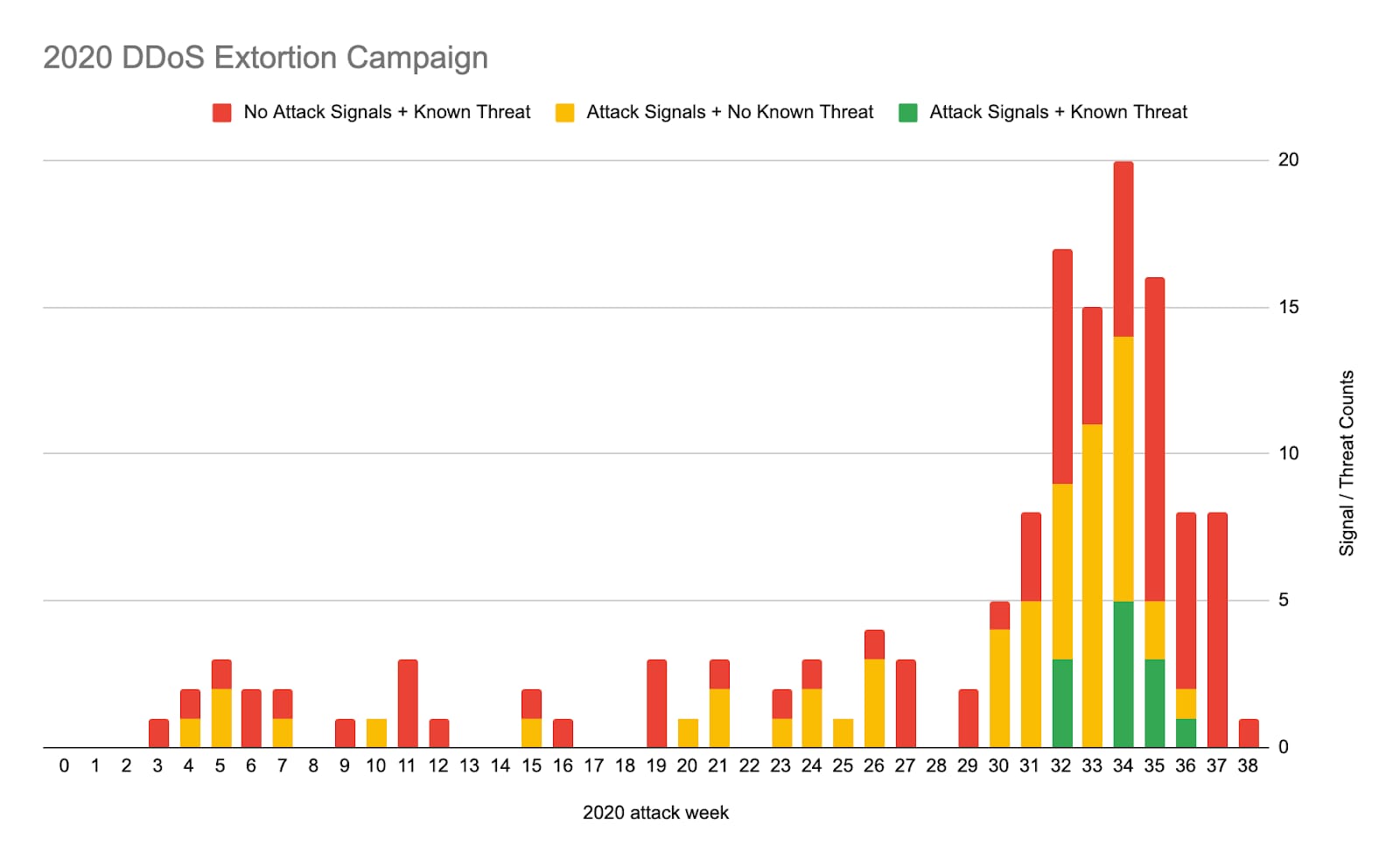

Fig. 3: Later attacks changed some of the protocols they used in an attempt to escape detection

Fig. 3: Later attacks changed some of the protocols they used in an attempt to escape detection

The game continues

This extortion DDoS campaign is not over. Just like a good poker player will change their style to throw off an opponent trying to decide on a bet, the criminals behind this campaign are changing and evolving their attacks in order to throw off defenders and the law enforcement agencies that are working to track them down. They might go quiet in the near future, but if we let the past predict the future, it's certain they'll be back for another go all too soon.

These attacks aren't unique, which makes definitively declaring them part of a specific campaign difficult. This is further obscured by the number of copy cats that mimic the text and style of the extortion attempts, with no direct connection to the "real" Fancy Bear and Armada Collective organizations.

Fig. 4: Similar attacks and emails have been seen prior to August, but the spike in related attacks is clear when stacked

Fig. 4: Similar attacks and emails have been seen prior to August, but the spike in related attacks is clear when stacked

Conclusion

Over 90% of these attacks can be defended against with automated controls and rules. The attacks themselves aren't new; they're using known vectors. An organization with the proper defenses in place and configured to match their environment can treat many of these attacks as a bluff. Unfortunately, many organizations either don't have the appropriate defenses or haven't enabled them for various reasons. Multiple organizations have needed to take emergency actions in order to protect themselves during this campaign.

The largest of these attacks exceeded 200 Gbps, which is, at best, difficult to combat without a dedicated solution, and preferably a partner organization like Akamai. These attacks have been global in nature. No matter where your organization is headquartered, if you receive an extortion email, please contact local law enforcement. The more they have to work with, the more likely it is the criminals will be stopped.