Edge DNS and the Top-Level Domain Hosting

Introduction

DNS is critical to website availability — yet it’s commonly viewed as an isolated, opaque internet service. Despite incorporating similar CI/CD practices for traditional application code, IT departments have historically not as readily embraced automated DNS workflows or transparent version control systems for zone updates. In addition, the logistics required to resolve a hostname are often an afterthought during a standard release cycle, and protocol expertise can be siloed to limited stakeholders as a result.

However, the recent introduction of APIs for both registrars and providers has led to more widespread adoption of “DNS as code” workflows, as record updates can now be published more efficiently with the help of DevOps technologies. In addition, dynamic DNS platforms such as Akamai Global Traffic Management offer application owners additional tools to improve site performance and reliability via intelligent handout decisions.

To accompany these enhanced automated capabilities, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) opened the top-level namespace to the public, so organizations can acquire their own top-level domain (TLD) — such as .akamai — in the DNS hierarchy. Once viewed as a specialized, restricted component of site availability, DNS continues to evolve into a more open and democratic protocol for developers and business stakeholders alike.

But even as DNS trends toward greater accessibility and transparency, the technical underpinnings that govern a domain’s lifecycle remain a mystery to many in the IT world. Although most of these professionals are familiar with purchasing a domain, the logistics required to manage ownership records in a TLD zone are less clear, since traditional companies have only recently been afforded this opportunity.

This article will focus on the protocols and processes required to fulfill domain transactions, and illustrate how Akamai Edge DNS can help applicants meet ICANN’s intensive requirements for hosting records in the apex namespace.

Registrars, registrants, and registries

Three parties are primarily involved with domain transactions: registrars, registrants, and registries. Registrars, such as GoDaddy or Google Domains, provide an accessible interface for members of the public to complete domain purchases. Meanwhile, a registrant is any person who has successfully acquired a domain via these registrar channels. Registries own the records database that is continually referenced as the single authoritative source by every registrar. Registries also oversee the TLD DNS zone, so queries can be successfully delegated to the registrant’s nameservers. Namespaces such as “.com” are solely managed by a single registry. However, multiple registrars can sell domains under the same namespace.

The Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP) orchestrates domain transactions between registrars and registries. EPP is built on TCP and relies on XML schema to programmatically exchange the necessary information between these two parties when a domain is acquired — including the registrant’s contact information and nameserver details.

However, when a registry finalizes a purchase in their database, the update is not proactively broadcasted via a push model. As such, the other registrars selling the domain will only realize the new ownership status once another interested user invokes a separate EPP call to discover the domain’s availability. Once an EPP response confirms a domain is already owned, registrars will update their interface accordingly.

While EPP defines how data pertinent to domain purchases is formatted and transferred, there is no set standard for how the registry should consume these calls to update their back-end database, so this architecture will be designed and maintained on the basis of the registry’s architectural preferences. Similarly, the registry is responsible for developing a mechanism to sync the database with the TLD zone file in an efficient, scalable manner.

Purchasing a new TLD

The previous section applied to users looking to purchase subdomains from an existing apex space (e.g., newdomain.com). However, in 2012, ICANN announced an initiative to allow established corporations, nonprofits, and government institutions to apply for apex domains called generic top-level domains (gTLDs; .newdomain), as organizations are discovering new business applications for procuring their own namespace.

The process to acquire a new top-level space isn’t as straightforward as purchasing a domain from a registrar. ICANN requires a substantial application fee, and applicants must demonstrate they’re capable of performing the many responsibilities of a functioning registry, including hosting a top-level zone in DNS. All applicants are required to meet these expectations, even if the organization has no intention of selling domains to the public.

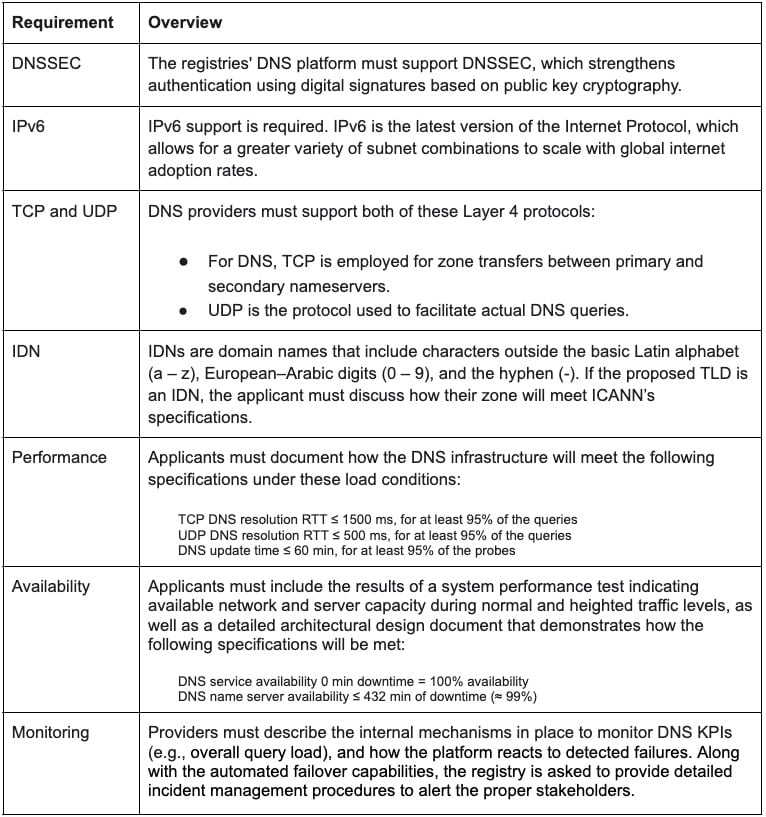

The table below highlights some of the DNS criteria ICANN requires applicants’ nameservers to satisfy to successfully reserve a gTLD.

Some of the DNS criteria required by ICANN to successfully reserve a gTLD

The ICANN application solicits details on how the applicant’s DNS platform will meet these criteria, and answers are graded on a 0–3 numerical scale, though certain sections are evaluated on a more binary rubric. While the table focuses on DNS criteria, the applicant must also address other technical areas specific to registry record-keeping operations, such as EPP support and the WHOIS protocol. Finally, along with the technical and operational components of the application, a financial assessment and background check are mandatory stipulations.

Once all the necessary materials are submitted and evaluated, ICANN will administer a cumulative pass/fail result, but the applicant is entitled to file an extended evaluation request to clarify any perceived shortcomings should their initial application fail to meet the mandatory minimum score. However, if the extended evaluation process still does not satisfy ICANN’s requirements, the application will not move forward. More details on the overall scoring system can be found in the Applicant Guidebook on the ICANN website.

Once the application is approved, the registry is subjected to a series of predelegation technical tests to determine if the provider’s DNS architecture supports the various protocol requirements in practice (DNSSEC, IPv6, EPP, WHOIS, etc.). If these validations prove successful, ICANN will provide the registry operator with a unique delegation token to access ICANN’s Root Zone Management (RZM) system, and the root zone will be updated to delegate queries for the new gTLD once the applicant submits the pertinent nameserver details in this interface.

Akamai and TLD hosting with Edge DNS

While registries often rely on their own nameservers, many partner with a third party to meet ICANN’s technical requirements, a service that Akamai now offers with Edge DNS. With more than 1,500 points of presence scattered across the globe and a 100% uptime service-level agreement, Edge DNS is uniquely qualified to host TLD zones for registry services.

The Edge DNS platform is built on intelligently deployed anycast networks, so queries are consistently routed to a nearby, available nameserver for optimal performance and reliability. Run on proprietary software, Edge DNS is not susceptible to the many well-known vulnerabilities that plague BIND, and standard customer traffic typically consumes less than 1% of total nameserver capacity, leaving malicious actors little opportunity to successfully administer distributed, volumetric attacks. As a result, registries can confidently turn to Edge DNS to satisfy ICANN’s scale, performance, and security requirements for gTLD hosting.

ICANN does not provide a standard for how registries should manage nameserver records in their TLD zone, but the volume of these transactions typically necessitates an automated workflow. If a registry chooses to configure Edge DNS as the primary DNS provider, Akamai supports an open API to perform zone updates programmatically, along with an easy-to-use command line interface.

However, registries also have flexibility to implement a secondary model with Edge DNS if admins prefer to work within their existing DNS infrastructure’s framework to perform changes — these changes would then automatically propagate to the Edge DNS network via zone transfers. Thus, with Edge DNS, registries have multiple viable options to seamlessly execute record updates at scale.

In addition, Edge DNS supports DNSSEC to protect against DNS forgery, alongside other protocol RFC requirements outlined in the ICANN application, including IPv6 and IDN. The platform also comes equipped with advanced monitoring and failover mechanisms, so the network can seamlessly recover in the unlikely event of hardware malfunctions, such as disk or network card failure. Registry employees can even view traffic and availability metrics in prebuilt dashboards available in Akamai’s portal.

Conclusion

Once a relatively static question/answer protocol, DNS continues to embrace further dynamism and automated capabilities that extend beyond a simple “phonebook for the internet.'' More and more developers are becoming comfortable with programmatic record management practices, and application owners are now leveraging intelligent handout decisions to further improve site performance and reliability.

In an effort to make DNS more accessible, ICANN recently launched an initiative to allow organizations in good standing to purchase a TLD space. However, overseeing an apex zone in DNS poses unique performance, security, and reliability challenges given the potential volume of ongoing record transactions and incoming queries. Thankfully, existing and aspiring registries can now turn to Akamai Edge DNS, which offers the scale, flexibility and functionality to meet the requirements of hosting zones in the top level namespace.

While the trend towards heightened accessibility and automation is likely to continue, it is difficult to predict what future DNS innovations are on the horizon. However, as with gTLD hosting, Akamai Edge DNS will continue to keep pace with the challenges and opportunities that will inevitably surface as the protocol evolves.

Explore more DNS-oriented solutions from Akamai

Akamai is continuously expanding our Edge DNS platform to enable a greater range of services for domain owners. With Akamai, you can:

Achieve domain stability and resilience with Akamai Edge DNS service

Load balance your data centers, cloud deployments, and CDNs with Global Traffic Management, Akamai's cloud-based global server load balancer

Scale your application with Layer 7 load balancing from Akamai's Application Load Balancing Cloudlet

Perform DNS security checks for all devices across your network to ensure domain names are safe with Akamai Secure Internet Access

Access more Akamai resources by joining our community

Join Akamai’s Developer Hub to learn API and DevOps-aligned DNS solutions that enable cloud-to-cloud innovation

Still have DNS questions? Get in touch with us today.