The Vollgar Campaign: MS-SQL Servers Under Attack

Guardicore Labs team has recently uncovered a long-running attack campaign which aims to infect Windows machines running MS-SQL servers. Dating back to May 2018, the campaign uses password brute force to breach victim machines, deploys multiple backdoors and executes numerous malicious modules, such as multifunctional remote access tools (RATs) and cryptominers. We dubbed the campaign Vollgar after the Vollar cryptocurrency it mines and its offensive, vulgar behavior.

Having MS-SQL servers exposed to the internet with weak credentials is not the best of practices. This might explain how this campaign has managed to infect around 3k database machines daily. Victims belong to various industry sectors, including healthcare, aviation, IT & telecommunications and higher education.

A full list of IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) as well as a detection script can be found in Guardicore Labs Campaigns repository.

Victim analysis: long infection periods

The first incident of this campaign appeared in May 2018 in Guardicore’s Global Sensors Network (GGSN), a network of high-interaction honeypots. During its two years of activity, the campaign’s attack flow has remained similar – thorough, well-planned and noisy; we describe the different steps of the attack chain in the next section. A peak in the number of incidents in last December drew us to closely monitoring the campaign and its impact.

Overall, Vollgar attacks originated in more than 120 IP addresses, the vast majority of which are in China. These are most likely compromised machines, repurposed to scan and infect new victims. While some of them were short-lived and responsible for only several incidents, a couple of source IPs were active for over three months, attacking the GGSN dozens of times.

By analyzing the attacker’s log files, we were able to obtain information on the compromised machines. With regards to infection period, the majority (60%) of infected machines remained such for only a short period of time. However, almost 20% of all breached servers remained infected for more than a week and even longer than two weeks. This proves how successful the attack is in hiding its tracks and bypassing mitigations such as antiviruses and EDR products. Alternatively, it is very likely that those do not exist on servers in the first place.

We have noticed that 10% of the victims were reinfected by the malware; the system administrator may have removed the malware, and then got hit by it again. This reinfection pattern has been seen by Guardicore Labs before in the analysis of the Smominru campaign, and suggests that malware removal is often done in a partial manner, without an in-depth investigation into the root cause of the infection.

Attack flow: vulgar, thorough & competitive

The Vollgar attack chain demonstrates the competitive nature of the attacker, who diligently and thoroughly kills other threat actors’ processes.

Initial breach

The attack begins with MS-SQL brute force login attempts. Once the attacker breaks in, a series of configuration changes is performed to the database to allow future command execution.

EXEC sp_configure 'show advanced options', 1;RECONFIGURE;

EXEC sp_configure 'xp_cmdshell', 1;RECONFIGURE;

exec sp_configure 'show advanced options', 1;RECONFIGURE;

exec sp_configure 'Ad Hoc Distributed Queries',1;RECONFIGURE;

exec sp_configure 'show advanced options', 1;RECONFIGURE;

exec sp_configure 'Ole Automation Procedures',1;RECONFIGURE;

exec sp_addextendedproc xp_cmdshell,'xp_cmdshell.dll'

Following these settings changes, the attacker performs a series of steps to make the system as out-of-the-box as possible. For example, the attacker validates that certain COM classes are available – WbemScripting.SWbemLocator, Microsoft.Jet.OLEDB.4.0 and Windows Script Host Object Model (wshom). These classes support both WMI scripting and command execution through MS-SQL, which will be later used to download the initial malware binary. The Vollgar attacker also ensures that strategic files such as cmd.exe and ftp.exe have execution permissions.

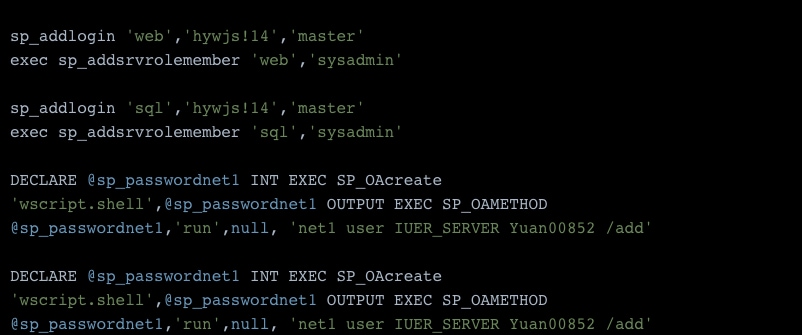

Planning ahead, the attacker sets multiple backdoor users on the machine – both in the MS-SQL database context and in that of the operating system. In both cases, the users are added to the administrators group to “arm” them with elevated privileges.

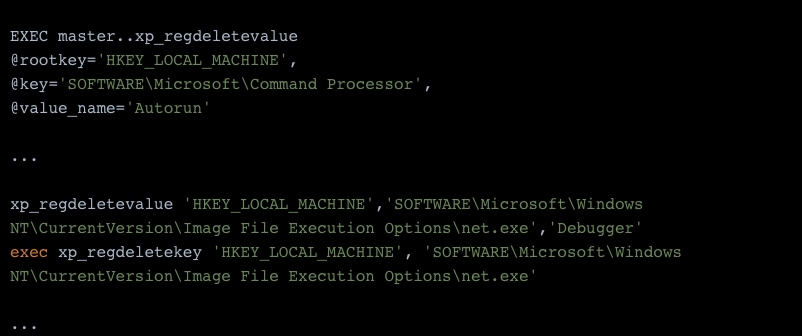

Being the only attacker on a machine is powerful – your malware gets the most resources, such as bandwidth and CPU power, and access is valid only through your backdoors. Therefore, the Vollgar attacker puts many efforts into both eliminating other threat actors’ activity and removing their traces. For example, Vollgar deletes the key HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Command Processor\Autorun, frequently used by attackers for persistence.

In addition, many values from Image File Execution Options are removed. Normally, this section in the registry is used to attach a certain process – usually a debugger – to other executables. Threat actors exploit this functionality to run malicious processes along with system executables. By deleting these values, Vollgar ensures that no other malware is attached to legitimate processes, such as cmd.exe, ftp.exe, net.exe and Windows scripting hosts such as wscript.exe and cscript.exe.

Downloaders

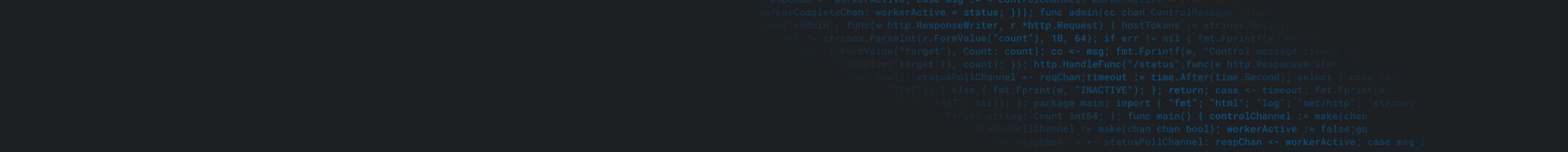

To prepare for possible failures, the attacker writes three separate downloader scripts – two VBScripts downloading over HTTP and one FTP script. Each downloader is executed a couple of times, every time with a different target location on the local file system. This thoroughness is somewhat unusual among other attack groups, who often look for the fastest route to their goal.

Attacker infrastructure: an omni-compromised machine

Vollgar’s main CNC server was operated from a computer in China. The server, running an MS-SQL database and a Tomcat web server, was found to be compromised by more than one attack group. In fact, we found almost ten different backdoors used to access the machine, read its file system contents, modify its registry, download and upload files and execute commands. Nevertheless, the machine was “business as usual”, running the database service as well as benign background processes. Malicious activity can be seen among running tasks, active sessions and lists of users with administrative privileges – yet it somehow escaped the owners of this server.

The attacker held their entire infrastructure on the compromised machine. Among the files was the MS-SQL attack tool, responsible for scanning IP ranges, brute-forcing the targeted database and executing commands remotely. In addition, we found two CNC programs with GUI in Chinese, a tool for modifying files’ hash values, a portable HTTP file server (HFS), Serv-U FTP server and a copy of the executable mstsc.exe (Microsoft Terminal Services Client) used to connect to victims over RDP.

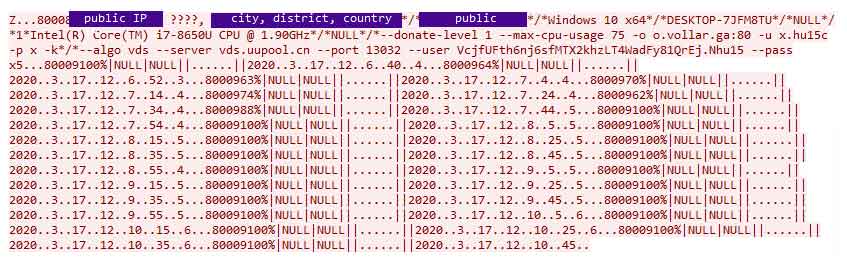

Upon connection from an infected client, the CNC receives from the client several identifying data – its public IP, geolocation – city, district and country, operating system version, computer name and CPU model. Two command lines for cryptominer execution are also sent to the server, probably for monitoring purposes.

As mentioned earlier, we found two CNC platforms used by the attacker. These two platforms were developed by different vendors, but offer a similar variety of remote control capabilities to the attacker who controls them: downloading files, installing new Windows services, keylogging, screen capturing, running an interactive shell terminal, activating the camera and the microphone, initiating a DDoS attack, and more.

Hosting companies host abusive business

The Vollgar infrastructure is based on abused domain names and shell companies. The attacker uses this infrastructure to host malicious payloads and operate the campaign’s command-and-control bases.

The attacker freely uses internet services which are ripe for abuse; the domain vollar.ga uses the .ga top-level domain (TLD), which can be registered for free. Like many other free TLDs, .ga is wildly abused by malware providers.

Many of the CNC servers are hosted on odd hosting services. One set of observed CNC servers all belong to a specific autonomous system number (ASN) AS133115, HK Kwaifong Group Limited. Despite its large size, this AS is registered with a private email account, kwaifong33@gmail.com. The email address appears on multiple additional ASNs, such as AS133073, registered to www.glovine.com.au – a completely disabled website.

The ASNs seem to share many of their IP ranges with a hosting company named CloudInnovation Infrastructure. A quick look at their website – cloudinnovation.org – reveals an obviously nonexistent business. However, the company owns a large collection of illegitimate domains.

These are just a few examples of different hosting services which clearly help provide a safe haven for fraudulent activity. The next section describes the malware modules hosted on the attacker’s servers and how these modules communicate with the attacker’s backend.

Malware – spawning multiple RAT modules

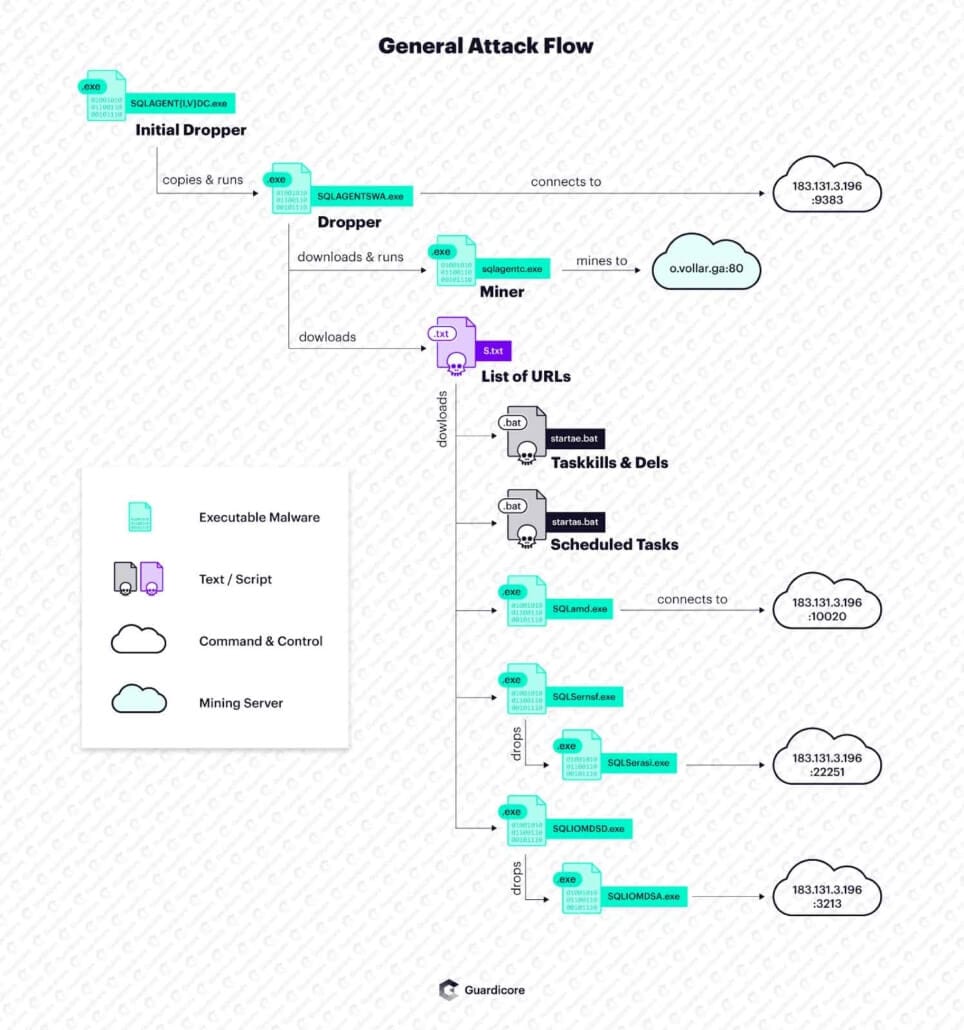

The initial payload, named SQLAGENTIDC.exe or SQLAGENTVDC.exe, starts by running taskkill on a long list of processes, with the goal of eliminating competitors and earning more computing resources. These processes include Rnaphin.exe, xmr.exe, and winxmr.exe, to name a few. Then, the payload copies itself to the user’s AppData folder and executes the copy. The new process checks for internet connectivity, then queries Baidu Maps to obtain the victim’s IP and geolocation which it later sends to the CNC. Then, a couple of additional payloads are downloaded onto the infected machine – multiple RAT modules and an XMRig-based cryptominer.

Each RAT module attempts to connect to the CNC server on a different port. Ports we’ve seen include 22251, 9383 and 3213. It is fair to assume that the simultaneous connections are for redundancy in case one of the CNCs is down. The communication between the client and server starts with an initial report of information, then continues with periodic heartbeats once every ten seconds.

The attacker is mining both Monero and an alt-coin named VDS, or Vollar. This is an unusual cryptocurrency, combining elements of Monero (full privacy) and Ethereum (smart contracts), pegged relatively close to the dollar.

Detection & mitigation

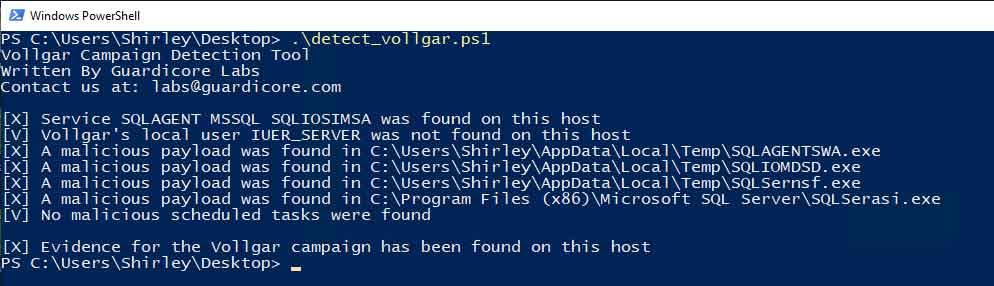

The Vollgar campaign targets Windows machines running MS-SQL servers which are internet-facing. To check if your Windows machine has been infected, Guardicore Labs provides an open-source Powershell script to detect Vollgar’s tracks and IOCs. The script along with execution instructions can be found in the campaign’s IOCs repository.

It is highly recommended to not expose database servers to the internet. Instead, they need to be accessible to specific machines within the organization through segmentation and whitelist access policies. We recommend enabling logging in order to monitor and alert on suspicious, unexpected or recurring login attempts.

The majority of attack campaigns, and Vollgar included, involve network communication to CNC servers. Outgoing communications to such destinations can and should be blocked; Guardicore offers a Threat-Intelligence Firewall, based on Guardicore Reputation Service, for exactly this type of protection.

If infected, we highly recommend to immediately quarantine the infected machine and prevent it from accessing other assets in the network. It is also important to change all your MS-SQL user account passwords to strong passwords, to avoid being reinfected by this or other brute force attacks.

Little prey; many predators

There is a vast number of attacks targeting MS-SQL servers. However, there are only about half-a-million machines running this database service. This relatively-small number of potential victims triggers an inter-group competition over control and resources; these virtual fights can be seen in many of the recent mass-scale attacks.

What makes these database servers appealing for attackers apart from their valuable CPU power is the huge amount of data they hold. These machines possibly store personal information such as usernames, passwords, credit card numbers, etc., which can fall into the attacker’s hands with only a simple brute-force.

Unfortunately, oblivious or negligent registrars and hosting companies are part of the problem, as they allow attackers to use IP addresses and domain names to host whole infrastructures. If these providers continue to look the other way, mass-scale attacks will continue to prosper and operate under the radar for long periods of time.