REvil Resurgence? Or a Copycat?

Written by: Larry Cashdollar, Akamai Security Intelligence Response Team

Executive Summary

Akamai researchers have been monitoring a distributed denial of service (DDoS) campaign against one of Akamai’s customers claiming to be associated with the infamous ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) group, REvil.

The attacks so far target a site by sending a wave of HTTP/2 GET requests with some cache-busting techniques to overwhelm the website.

The requests contain embedded demands for payment, a bitcoin (BTC) wallet, and business/political demands.

The attempts seem smaller than previous similar campaigns that claim to be launched by REvil and seem to have a political purpose associated with the extortion attempt, which is something we haven’t previously observed.

The BTC wallet currently has no history and is not tied to any previously known BTC wallets used by REvil.

Introduction

The infamous ransomware group REvil is well-known among the security community, and with good reason. They were brought into the spotlight after being credited for the Kaseya ransomware attack in 2021; they were also responsible for the crippling attack on JBS in the same year. REvil was reportedly dismantled in March 2022 by the Russian government, who took actions targeting REvil members, including apprehending one of the members who was responsible for helping launch the incredibly disruptive campaign against Colonial Pipeline.

In the last week, the Akamai Security Intelligence Response Team (SIRT) was made aware of a Layer 7 attack on one of our hospitality customers by a group claiming to be REvil. In this post, we are going to explore the attack, as well as compare this attack to previous attacks purportedly linked to the REvil group.

The attack

On May 12, 2022, an Akamai customer alerted the SIRT team of an attempted attack by a group claiming to be associated with REvil. We immediately began analyzing the data and cross-referencing our other attack data to see if we could corroborate or dispute this claim.

This attack was a coordinated DDoS attack, with traffic peaking at 15 kRps, that consisted of a simple HTTP GET request in which the request path contained a message to the target containing a 554-byte message demanding payment. The message dictated that in order for the attacks to cease, BTC needed to be transferred to a wallet address. There was also an additional geospecific demand, requesting the targeted company cease business operations across an entire country. If the targeted company did not comply with the business/political demands and did not pay the extortion by the desired timeline, a follow-up attack was threatened that would affect business operations globally.

This campaign followed a similar pattern publicly reported by Imperva, which included the string “revil” in the URL as part of the extortion message directed at operations teams and executives of the targeted company.

Attack details and indicators of compromise

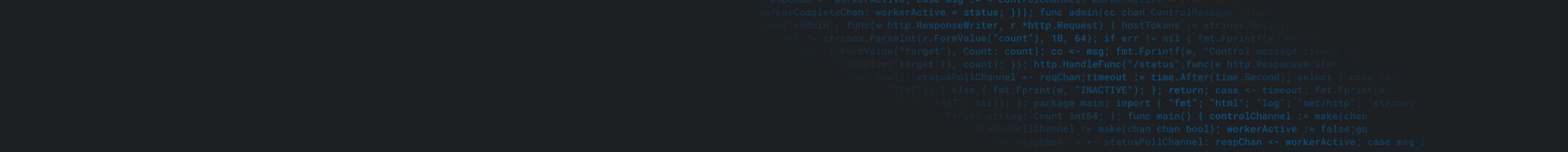

Cache busting

The request path that contained the extortion demand was static, but also included a randomly generated unique 8-character string appended to the end of it, as well as an additional unique 8-character query string. This is a typical cache-busting technique in an effort to make all requests unique so that they’ll bypass caching and result in a request that must be retrieved from the origin web server.

HTTP headers

Additionally, the “Accept” request header contained a long static list of accepted media types across all requests during the attack. This combination and their order, which is somewhat unique, could potentially assist in fingerprinting attack sources during an attack event.

"Accept": "text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.9"

Also worth noting is the User-Agent request header. Throughout the attack event a single static User-Agent string with no variation was observed from all attack sources:

"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/101.0.4951.54 Safari/537.36"

The HTTP GET request headers are also out of order (when compared with “typical” patterns), potentially indicating a custom-developed DDoS attack tool. It’s possible that these values might change between campaigns, so simply writing signatures for these patterns might not benefit defenders from an indicator of compromise (IoC) standpoint.

During this attack campaign, these values remained static from thousands of attack sources, meaning defenders might be able to isolate similar patterns as part of their signal-to-noise identification and signature writing and/or blocking processes.

Proxies and routers

While the HTTP headers remained static during the attack’s duration, the IPs participating in the attack were fairly well-distributed. Diving into attack sources, a wide swath of the participating IPs appeared to be either MikroTik devices or servers that had proxying services. Looking at the proxy nodes, they appeared to be somewhat locked down, as they required at least a username and password to leverage the proxying capabilities. These weren’t wide open proxies on the internet that someone could find and blindly leverage; some level of coordination was required between the attacker and the proxying system, and access to an existing proxying botnet was most likely leveraged and likely purchased.

The Meris botnet

With the number of MikroTik devices identified in the attacking sources, there was an assumption that this could be an attack supported by the MikroTik-based Meris botnet. Although this might be the case, it’s hard to confirm or deny this claim based on the information that was collected during the attack. Additionally, the non-MikroTik attack sources appeared to be using proxying services that were secured in a manner similar to what we’ve seen used by the Meris operators as the campaign has evolved.

Historically, Meris has been linked to record-setting and eye-watering levels of DDoS attack capabilities. Previous attacks have seen more than 2 Tbps floods clocking in at more than 2 mRps, leveraging HTTP pipelining and more sophisticated techniques. In contrast, this campaign comparatively peaked at approximately 15 kRps (or ~0.6% of reported peak rps) and seemed pretty unsophisticated.

The fact remains that a number of sources were MikroTik devices that were proxying attack traffic, and those proxies required prior knowledge of the username and password applied to the proxying service to be able to leverage them in this manner. It’s possible that the Meris botnet is “for sale”; it wouldn’t be the first malicious proxy network for sale on the underground. It’s also possible that it’s a “bring your own botnet” deal. In which case, we might be seeing a Meris-supported attack, launched by an attacker using less sophisticated or expansive tooling.

REvil’s typical modus operandi

In order to discuss whether this is a legitimate resurgence of REvil or a copycat, we must examine what is known to be REvil’s modus operandi and compare and contrast the two situations.

REvil has historically acted as a RaaS group that provides toolkits and expertise for hire to execute successful ransomware attacks against organizations. This is similar to the ransomware group Conti that we have discussed in great detail in a previous post.

This attack appears to be a “new” type of operation for the group. While there is precedent for REvil utilizing DDoS as a means of triple extortion, this technique strays from their normal tactics. The REvil gang is a RaaS provider, and there is no presence of ransomware in this incident. Typically, they’d gain access to a target network or organization and encrypt or steal sensitive data, demanding payment to decrypt or prevent information leakage to the highest bidders or threatening public disclosure of sensitive or damaging information.

Additionally, this attack appears to be somewhat politically motivated and related to a recent legal ruling about the targeted company's business model. In the past, REvil has openly proclaimed that they’re purely profit-driven: The escalatory nature of their attacks includes the destruction of data, or the promised releasing of sensitive information that could be damaging to an organization, with the hopes that those threats force compliance and payment. We haven’t seen REvil linked to political campaigns in any other previously reported attacks.

It’s possible that REvil is testing the waters of DDoS extortion as a profitable business model, but we think it’s more likely that we’re seeing the scare tactics associated with prior DDoS extortion campaigns recycled for a fresh round of campaigns. From DD4BC to Fancy Lazarus and now REvil, when it comes to DDoS extortion, scare tactics are the name of the game, and what better way to scare your victim into payment than leveraging the name of a notable group that strikes fear into the hearts of organizations’ executives and security teams across wide swaths of industry.

Conclusion

When a threat group changes its techniques, it could be a possible pivot into a new business model, a result of a dramatic change in its skill set, a schism among the group, or an unaffiliated copycat trying to leverage that group’s hype into easy money from short-sighted and emotionally reactive victims. Which of those cases we’re looking at here isn’t exactly clear at this point, but we wanted to raise awareness for other organizations that may fall victim to these techniques and campaigns going forward, especially because this potential REvil resurgence has been making headlines for the past month.

The Akamai SIRT’s goal is to track, detect, document, and publish new discoveries to protect the security and stability of Akamai, Akamai’s customers, and the internet as a whole. We will continue to monitor these attacks and update this blog accordingly.