Question Quiz—The Forgotten Scam

Overview

Over a year ago, Akamai’s threat research team published research regarding a widely-used phishing toolkit we referred to as the “Three Question Quiz”. It’s now time to review the evolution of the toolkit, the associated campaigns that we tracked in the wild, and the potential damage caused by those campaigns in the past year.

As part of our research, we tracked 1,161 websites hosting phishing toolkits between July 2019 and May 2020 that targeted 130 brands and had more than 5 million victims.

The number of victims observed during the research period shed more light on the phishing landscape, as well as the potential damage these phishing attacks can cause. Yet, it’s also important to clarify that the victim numbers we share almost certainly only represent the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the total victim pool, which we believe to be much higher.

The research reveals an increase of victims during the 2019 holiday season and the months of March to April 2020. According to our data, this time frame represents a combination of high motivation from threat actors to launch phishing campaigns, and victims being highly vulnerable - due to COVID-19 insecurities, such as those looking for deals or necessities.

This research also shows an impact to the targeted brands, leading to reputation damage and potential income losses, as customers walk away and share their negative experiences - unaware that the brand was being victimized too.

Originally, the kits we focused on had three questions, and as such we named them “three-question-quiz” scams. However, more recent research has shown an evolution of these kits and an expansion from three to four or more questions in a single session. As such, we’ll be referring to them as ‘question quiz” scams going forward.

Scam evolution—variants, mobile and IDN

As part of our continued research, we were able to see several variants of question quiz. It seems the design and interface of the kit was changed, and the source code was significantly updated. These changes didn’t alter the functionality of the website.

Figure 1: Question quiz variations

Figure 1: Question quiz variations

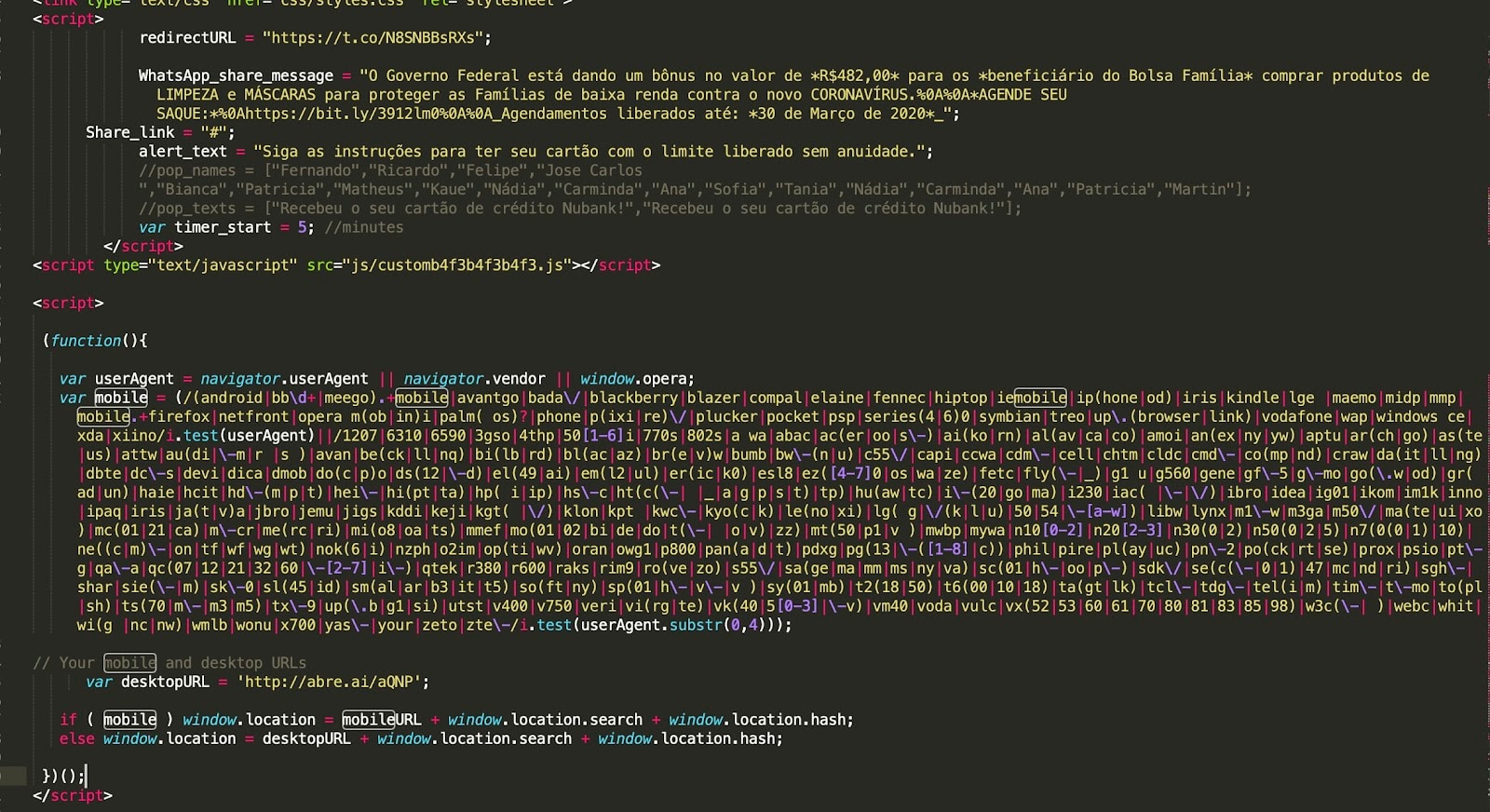

Some of the changes we tracked included victim filtering mechanisms, such as campaigns that are only targeting mobile devices. Those websites will lead non-mobile victims to benign destinations once they visit.

Image number 2: HTML code of mobile devices filtering

Image number 2: HTML code of mobile devices filtering

Another technique we observed is the usage of International Domain Names (IDN). IDN enables people around the world to use unicode domain names in local languages and scripts.

Using IDN in the context of phishing is known as a homograph attack. IDN domains deceive potential victims by presenting a seemingly harmless domain name in ASCII characters, when in reality the domain name and the destination are malicious.

In Figure 3, we see an example of a domain used as part of the question quiz campaign. The image shows a representation of that domain in IDN (on the right) and how it is being presented to potential victims (on the left).

Figure 3: Domain name in IDN and ASCII representation

Figure 3: Domain name in IDN and ASCII representation

Campaigns in the wild

Akamai tracked 1,161 question quiz scam websites, which lured in more than 5 million victims across the globe. However, we had limited geographic data, which leads us to believe the numbers may be much higher, making this a potentially massive campaign in terms of scale and scope.

According to the information collected over the last year, Akamai has seen campaigns targeting specific geographic regions and campaigns using language and brands that are specific to the victim’s location.

In other cases, we were able to see seasonal campaigns targeting events or activities, a notable example was a campaign targeting vacation hotspots just before the summer.

Another aspect of the research that sheds light on question quiz operations and how victims are targeted is seen in Figure 4. From the data, it appears that victims are targeted when they are vulnerable or searching for a general theme (such as vacations, holidays, etc.). There was a strong spike in attempts, for instance, in the days prior to Thanksgiving in the United States in 2019, when victims were likely looking for attractive deals on goods and services, coupons, and more.

Another example of this centers on the strong increase in the number of victims from mid-March until the end of April. We believe this trend is related to COVID-19, as criminals attempt to abuse the uncertainty and fear surrounding the pandemic to attract more victims.

An example of this was seen in a campaign analysis published earlier this year, where nearly 1 million victims in Brazil landed on question quiz websites promoting government payments.

Research shows that over 130 different brands were abused over the last year across a number of industries and market segments. What this data shows is that any brand can be leveraged by criminals for scams such as the question quiz.

Figure 4: Number of victims per day from sampled data

Figure 4: Number of victims per day from sampled data

Byproduct of phishing campaigns

According to our research, many of the websites participating in the question quiz campaigns were massively distributed and had a high engagement rate. As a result of this engagement, the websites became popular and highly-ranked by web analytics platforms. In some cases, we were also able to see the question quiz websites returned as top results in search engines, using common keywords that were related to the brand being abused.

The tactics used are called black hat search engine optimization, or blackhat SEO. It's a technique where threat actors will use commonly established and trusted SEO techniques for malicious means. The goal is to push their websites to the top of search rankings, in order to establish a larger reach and attract more visitors.

We believe that combination of blackhat SEO techniques, such as leveraging the abused brand in the domain name, website copy that included brand phrasing, topics, and other unique characteristics, as well as the steady stream of victims sharing links to the scam pages, and traffic volume, led to these domains becoming highly ranked in casual searches.

Figure 5: Web analytics of highly popular question quiz domain

Figure 5: Web analytics of highly popular question quiz domain

In Figure 5, we see a snapshot from SimilarWeb, an analytics platform, with an example of a question quiz website abusing a known clothing and sporting gear manufacturer. The stats show about one million visitors per month between July 2019 and October 2019, with more than 80% of the victims coming from a search engine.

Both examples show the power of blackhat SEO and how a scam can remain undetected for a long time. The longer a scam remains undetected, the more reach it has, and the more earning potential it provides to the criminals responsible. Highly popular domains can yield revenue, for example, by inclusion of advertisements or aftermarket sales based on the domain's popularity.

The scam that was forgotten

In order to understand why these question quiz scams are ranking so high in search engines and web analytics platforms, we checked classification scores of the websites with public threat intelligence resources. The result (Figure 6) was that 80% of the scam websites were not classified as malicious, and have – in a way – been forgotten.

Figure 6: Question quiz domains being detected by public sources

Figure 6: Question quiz domains being detected by public sources

The primary explanation that comes to mind as to why the detection rates are so low is that in many cases the scam is focused on information that isn't clearly valuable, or in some cases not viewed with a high degree of importance. As such, the problems are not mitigated. Enterprises are occupied by an onslaught of malware campaigns, data breaches, and web application attacks - constant high-priority fires that need to be put out - so it is easy to understand why scams that are focused on mostly non-sensitive information are forgotten about.

Summary

Phishing has evolved from being focused solely on credential abuse and drive-by downloads to a more lucrative kind of attack where the stolen good can be personal information that's used in analytic and data markets or repurposed to more targeted malicious activities. Moreover, the internet also offers the ability to generate revenue via advertisements and the associated traffic to the scam websites. Once the threat actor's malicious activity becomes widely distributed, they're rewarded indirectly by the forces that drive the internet itself.

As this research shows, phishing's potential impact also includes damage to the brand being abused, a type of damage that is not always tangible, so it is sometimes overlooked.