Purple Fox Rootkit Now Propagates as a Worm

by Amit Serper and Ophir Harpaz

Executive Summary

Purple Fox is an active malware campaign targeting Windows machines.

Up until recently, Purple Fox’s operators infected machines by using exploit kits and phishing emails.

Guardicore Labs have identified a new infection vector of this malware in which internet-facing Windows machines are being breached through SMB password brute force.

Guardicore Labs have also identified Purple Fox’s vast network of compromised servers hosting its dropper and payloads. These servers appear to be compromised Microsoft IIS 7.5 servers.

The Purple Fox malware includes a rootkit that allows the threat actors to hide the malware on the machine and make it difficult to detect and remove.

Introduction

During the last few weeks, the Guardicore Labs team has been tracking a new campaign distributing the Purple Fox malware. Purple Fox was discovered in March 2018 and was covered as an exploit kit targeting Internet Explorer and Windows machines with various privilege escalation exploits.

However, throughout the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, Guardicore Global Sensors Network (GGSN) detected Purple Fox’s novel spreading technique via indiscriminate port scanning and exploitation of exposed SMB services with weak passwords and hashes.

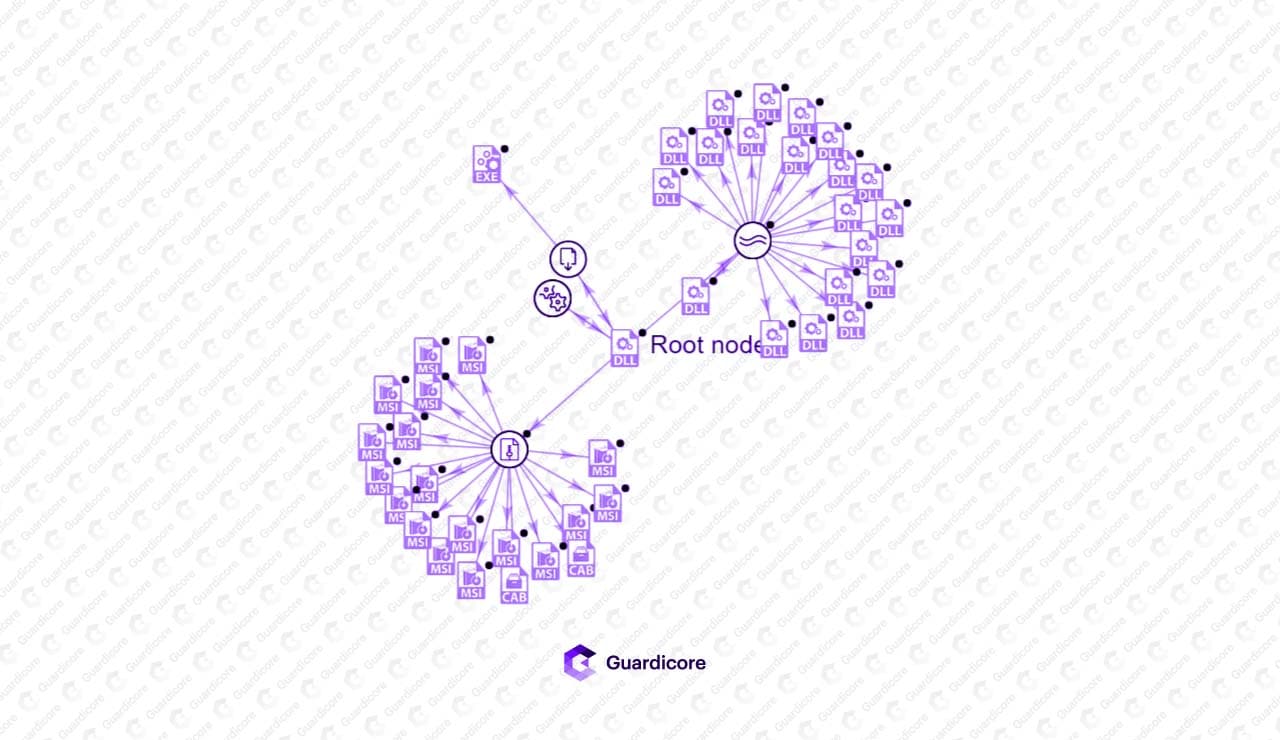

By leveraging the capabilities of GGSN, we were able to track the spread of Purple Fox. As can be seen in the figure above, May 2020 brought a significant amount of malicious activity, and the number of infections we have observed has risen by roughly 600%, amounting to a total of 90,000 attacks as of the writing of this blog post.

Although it appears that the functionality of Purple Fox hasn’t changed much postexploitation, its spreading and distribution methods — and its worm-like behavior — are much different than described in previously published articles. Throughout our research, we have observed an infrastructure that appears to be made of a hodgepodge of vulnerable and exploited servers hosting the initial payload of the malware, infected machines serving as nodes of those constantly worming campaigns, and server infrastructure that appears to be related to other malware campaigns.

In this blog post, we will detail our findings about the new worm activity and share our indicators of compromise (IOCs).

Attack analysis

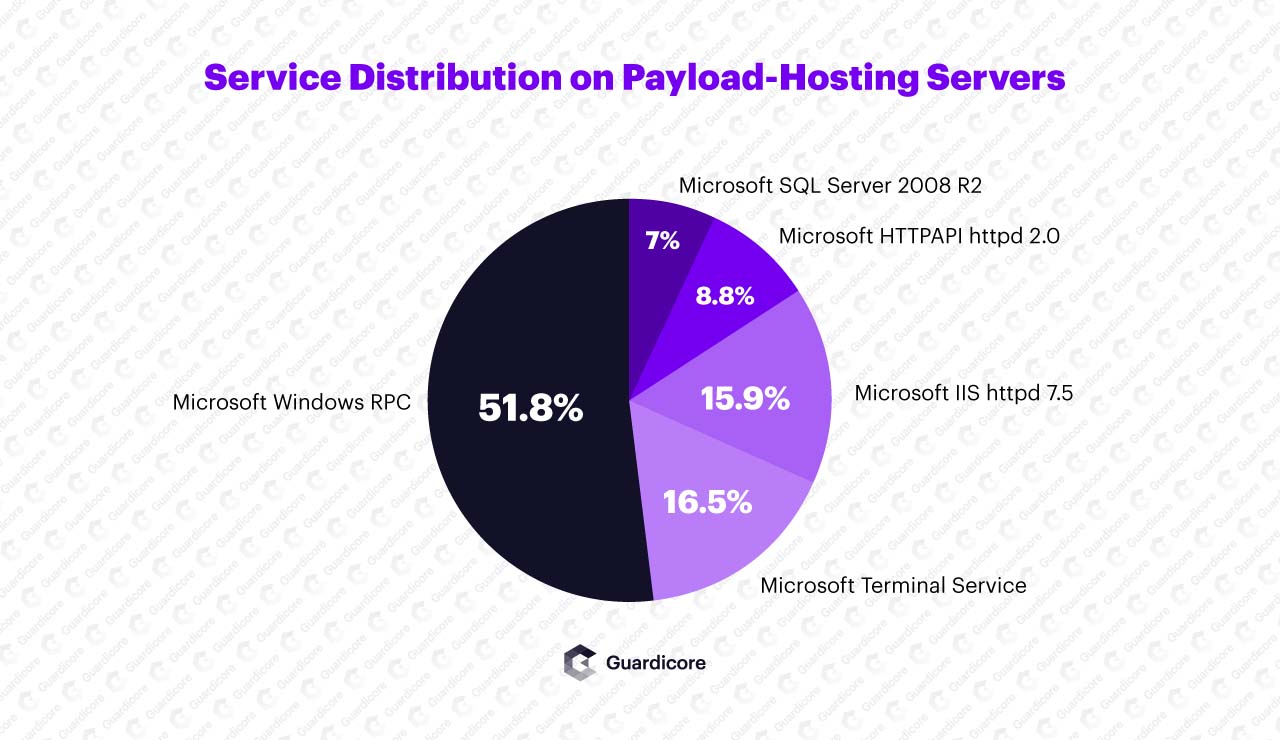

The attackers are hosting various MSI packages on nearly 2,000 servers (see IOCs in our IOC github repository), which to our assessment are compromised machines that were repurposed to host malicious payloads. Our assumption is based on scanning multiple servers, looking at the services that are hosted on them from the perspective of operating system versions, and server versions.

We have established that the vast majority of the servers, which are serving the initial payload, are running on relatively old versions of Windows Server running IIS version 7.5 and Microsoft FTP, which are known to have multiple vulnerabilities with varying severity levels.

According to our findings, there are two ways for this campaign to start spreading:

The worm payload is being executed after a victim machine is compromised through a vulnerable exposed service (such as SMB).

The worm payload is being sent via email through a phishing campaign (which could tie to the previously published findings about Purple Fox) that exploits a browser vulnerability. We have identified multiple samples that were submitted to VirusTotal through email scanners.

Once code execution is achieved on the victim machine, a new service whose name matches the regex AC0[0-9]{1} — e.g., AC01, AC02, AC05, etc. — will be created. The purpose of this service would be to establish persistence and to execute a simple command with a “for loop.” The purpose of this command would be to iterate through a number of URLs that contain the MSI that installs Purple Fox on the machine.

As can be seen in the screenshot from the Guardicore Centra platform, msiexec will be executed with the /i flag, in order to download and install the malicious MSI package from one of the hosts in the statement. It will also be executed with the /Q flag for “quiet” execution, meaning no user interaction will be required.

Once the package is executed, the MSI installer will launch.

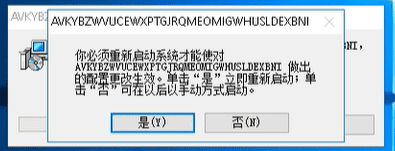

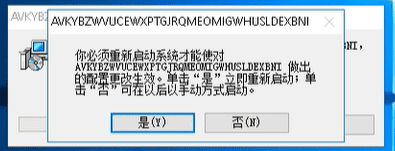

For analysis purposes, we have executed the MSI installer without the /Q flag (as if it’s being executed directly from an email attachment). The installer presents the following window:

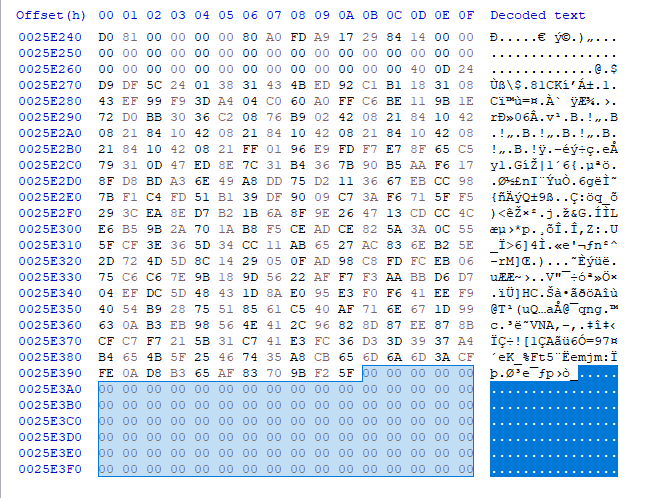

The installer pretends to be a Windows Update package along with Chinese text that roughly translates to “Windows Update” and random letters. These letters are randomly generated between each different MSI installer to create a different hash and make it a bit difficult to tie between different versions of the same MSI. This is a “cheap” and simple way of evading various detection methods such as static signatures. Additionally, we have identified MSI packages with the same strings but with random null bytes appended to them in order to create different hashes of the same file.

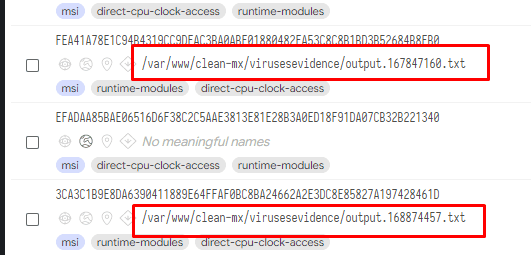

We were, however, able to find many different versions of the same MSI and its payloads, as can be seen in the following screenshot from VT graph.

As the installation progresses, the installer will extract the payloads and decrypt them from within the MSI package. The MSI package contains three files:

A 64bit DLL payload (winupdate64)

A 32bit DLL payload (winupdate32)

An encrypted file containing a rootkit

As a part of the installation process, the malware modifies the Windows Firewall by executing multiple netsh commands. The malware adds a new policy named Qianye to the Windows Firewall. Under this policy, it creates a new filter called Filter1 and under this filter, it prohibits ports 445, 139, 135 on both TCP and UDP from any IP address on the internet (0.0.0.0) to connect to the infected machine, we believe that the attackers are doing it in order to prevent the infected machine from being reinfected and/or to be exploited by a different threat actor.

Once the aforementioned files are being extracted, they will be executed.

This can be seen as the malware is executing the following commands:

netsh.exe ipsec static add policy name=qianye

netsh.exe ipsec static add filterlist name=Filter1

netsh.exe ipsec static add filter filterlist=Filter1 srcaddr=any dstaddr=Me dstport=135 protocol=TCP

netsh.exe ipsec static add filter filterlist=Filter1 srcaddr=any dstaddr=Me dstport=139 protocol=TCP

netsh.exe ipsec static add filter filterlist=Filter1 srcaddr=any dstaddr=Me dstport=445 protocol=UDP

netsh.exe ipsec static add filter filterlist=Filter1 srcaddr=any dstaddr=Me dstport=135 protocol=UDP

netsh.exe ipsec static add filter filterlist=Filter1 srcaddr=any dstaddr=Me dstport=139 protocol=UDP

netsh.exe ipsec static set policy name=qianye assign=y

netsh.exe ipsec static add rule name=Rule1 policy=qianye filterlist=Filter1 filteraction=FilteraAtion1

netsh.exe ipsec static add rule name=Rule1 policy=qianye filterlist=Filter1 netsh.exe ipsec static add filteraction name=FilteraAtion1 action=block

Additionally, the malware will install an IPv6 interface on the machine by executing the command:

netsh.exe interface ipv6 install

This action is taken in order to allow the malware to port scan IPv6 addresses, as well as to maximize the efficiency of the spread over (usually unmonitored) IPv6 subnets.

Important note: These commands can be used as indicators of behavior in order to check if your environment is compromised.

Additionally, these netsh commands have also appeared in previous campaigns and are not exclusive to this iteration of Purple Fox. These commands, specifically with the Qianye policy name, have been documented as a part of Rig Exploit Kit and NuggetPhantom.

The last step of Purple Fox’s deployment before restarting the machine is to load the rootkit that’s hidden inside the encrypted payload in the MSI package.

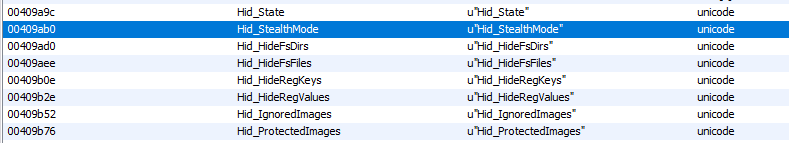

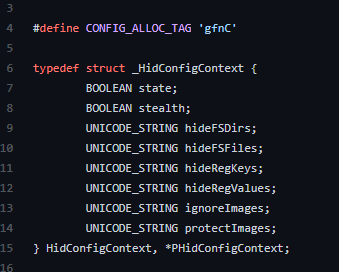

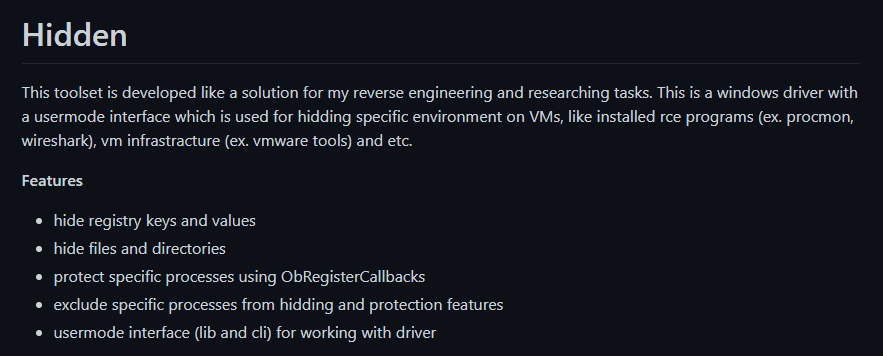

According to our analysis, the rootkit is based on the hidden open source rootkit project.

The purpose of this rootkit is to hide various registry keys and values, files, etc., as detailed by its author on the git repository. Ironically, the hidden rootkit was developed by a security researcher in order to conduct various malware analysis tasks and to keep all of these research tasks hidden from the malware.

This rootkit and its relationship with Purple Fox was detailed in this article by 360 Total Security.

Once the rootkit is loaded, the installer will reboot the machine in order to rename the malware DLL into a system DLL file that will be executed on boot. Since we executed the malware in our lab without the /Q flag, we were presented with the following window, which asks us to restart the machine:

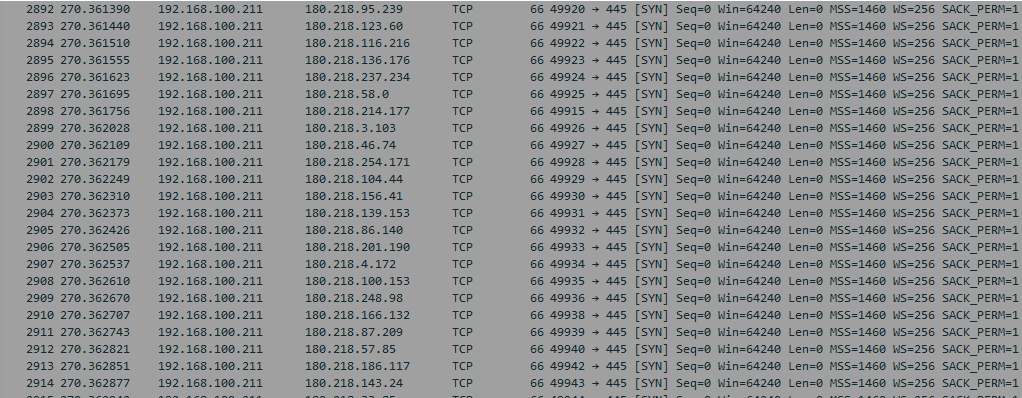

Once the machine is restarted, the malware will be executed as well. After its execution, the malware will start its propagation process: The malware will generate IP ranges and start scanning them on port 445.

As the machine responds to the SMB probe that’s being sent on port 445, it will try to authenticate to SMB by brute forcing usernames and passwords or by trying to establish a null session.

If the authentication is successful, the malware will create a service whose name matches the regex AC0[0-9]{1} — e.g., AC01, AC02, AC05, etc. (as mentioned before) — that will download the MSI installation package from one of the many HTTP servers and thus will complete the infection loop.