Protecting your Domain Names: Taking the First Steps

This blog was last updated on March 4, 2020 at 10:09 PM.

Everyone and everything on the Internet depends on the Domain Name System (DNS) being functional. The DNS has been a common vector for attacks in recent years, and 2019 seems to be no different. Many of these attacks have goals far more sinister than simply taking a company offline or defacing a website; reported attacks include redirecting some or all of an organization's domain to gain access to protected resources, intercept traffic, and even obtain TLS certificates for that domain. Organizations should perform regular DNS reviews and audits. The following guidelines provide a starting point for your review.

Why attack the DNS?

The DNS is critical to any organization with an online presence. Attacking domain names is a notable method to DoS (Denial of Service), deface, abuse or otherwise damage any Internet-connected organization. Domain names represent not only your brand but the way your customers interact with your business. In today's world, domain names are critical for web, voice, video, chat, APIs, and all the other services your company may offer or consume. In short, control of your domain names is essential to your business.

One of the most overlooked threats to your DNS presence is neglect. Many organizations take their DNS setup for granted, configuring it once and leaving it for all time. Adversaries leverage this neglect and the resulting weaknesses. Performing regular DNS reviews and audits is an essential preventative measure.

Where to start?

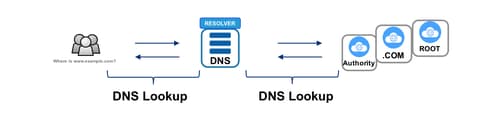

Adversaries can attack a DNS architecture through the DNS root zone, the DNS registries/top-level domains (TLDs) (e.g. .com, .net, .uk, .jp), the domain name registrars, the DNS name registrants(the entity for whom the zone is delegated), the DNS zone files, the authoritative DNS name servers, and recursive DNS resolvers. Attackers can also hijack routes to - or spoof IP addresses of - DNS servers. As you can see, this is a broad attack surface. The good news is that the DNS is built to be robust and there are many organizations focusing on DNS security, stability, and resilience .

The first area of focus is administration of the DNS zone (e.g. example.com). DNS zone administration is an area many organizations neglect in their security and network audits. Do not underestimate the scope and potential damage of an attack: access to a zone and/or the registrar enables redirecting inbound email, routing traffic through an attacker-controlled host, and even obtaining TLS certificates.

The domain name registrar and the DNS zone file

Among other things, the domain name registrar controls the list of a domain's authoritative name servers, or "delegations". These delegations consist of the hostnames and IP addresses of DNS servers that are authoritative for the domain in question. Authoritative DNS servers have a copy of the master zone file and answer DNS queries with the "authoritative answer" bit set. The rise of large-scale attacks in recent years has changed how domain owners operate their authoritative nameservers. Historically, most organizations operated their authoritative nameservers on their own systems. Today, organizations have more options. Some domain name registrars offer full-service packages where the registrar operates and maintains the full DNS configuration for a domain. For example, cloud-based providers such as Akamai's Edge DNS provide enhanced resilience to DDoS attacks, and simplified infrastructure management.

DNS review and audit exercise

News articles, Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), and government notices might push for you to "do a DNS audit," but the advice often ends there. The remainder of this post is a collection of topic areas an organization should review to assess their current DNS stance. These recommendations are based on Akamai's own experience, the work of ICANN's Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC), the DNS Operations, Analysis, and Research Center (DNS-OARC), and other DNS experts.

Review access to domain name registrars

Review the current domain administrators in your organization as seen by your registrar, and make sure they match your expectations. Review all the domains configured with your registrar and ensure that you know who in your organization has access to the registrar's online portal. Confirm with those users that they have access to the registrar's online portal. If you have domains registered with multiple registrars, make sure you repeat this exercise for every registrar. You may wish to consider consolidating your registrations with a single registrar. Also, take the opportunity to verify that all of your domains are accounted for in your audit of registrars - someone may have registered a domain using a personal account which could lead to a loss of control if they leave your organization.

Adversaries will take advantage of an organization's DNS neglect. They will find accounts that are not properly maintained and compromise them. Reviewing, updating, and documenting who has access to each zone at each registrar is the first step.

Review DNS roles and responsibilities

A good guideline for security is the principle of least access: people should have the lowest level of access required to do their job. Are the users with access to the registrar the people whose job function requires that access? In addition to a one-time review, schedule a recurring review of everyone's level of access. Also, ensure that there are at least two people with access to each registrar portal; if one of the administrators were to leave, the loss of access could be catastrophic to an organization.

Remember that attackers often leverage social media as part of phishing attempts. They can easily target high-profile employees on social media platforms, knowing that organizations may forget to remove registrar access after re-organizations, layoffs, or retirement.

Employee transitions

An organization's pre-termination process should include a review of user roles. As part of that review, the organization should audit the employee's access to resources like registrar accounts or DNS cloud providers, and terminate any access. Access should be granted to a replacement or successor employee as soon as reasonable.

The termination process should also trigger rotation or revocation of all secrets to which the departing employee had access. In addition to passwords, this should include Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) tokens, verbal authentication passphrases, and any lists of authorized employees the registrar may have on file. These changes should be standard practice, regardless of the circumstances of the employee's departure. They do not besmirch the departing employee, but rather reflect the threat to the organization.

Update all registration information

Next, look at the contact information associated with your registered domain names. Ensure the expiration dates for each domain name are sufficiently far in the future (at least one year is a recommended target) and any options, such as automatic renewal, are set appropriately. A domain name that expires unexpectedly can result in significant financial cost, and in the worst case scenario, can be irretrievably lost or registered by a competitor.

Domains also typically have four points of contact: the registrant, technical, administrative, and billing contacts. Your registrar may send certain types of communication to only one of those roles, and in some disputes, the registrant contact usually takes precedence. Ensure that all contact information is up to date - contact updates are often overlooked when organizations grow, shrink, move, or are acquired.

Use roles for domain registration information

To aid in managing domain registration contact information, organizations often use a role account for all four required contacts of domains. Implementation of the role account differs from organization to organization, but the basic idea is to have a tightly restricted mailing list set up to which all domain registration correspondence can be sent. Often the roles will be named either "Domain Administrator" or "Hostmaster" with the organization's headquarters contact information listed for the address, phone, and fax number. Be sure that legitimate phone calls and faxes directed to those numbers will still reach the DNS administrator. Using a role rather than a named person allows for job responsibilities to change or people to be added and removed without major updates occurring at the registrar. If using a mailing list, your regular audit should review the employees subscribed to the mailing list to limit potential misuse.

Don't use personal email addresses

Personal email addresses should never be used as points of contact for corporate, governmental, or organizational domain administrators. As part of the review process, make sure personal email addresses are never used for domain contact information or registrar access accounts.

Using an employee's personal email address (e.g. joe@gmail.com) as a point of contact effectively hands over control of the domain to that employee. In addition to the fact that you don't know what sort of security practices your employees use on their personal email accounts, you're opening yourself up to retaliatory action by a disgruntled current or former employee. All your domain contact points should include email addresses controlled by your organization, or a parent organization.

Using an employee's organizational or corporate email address (e.g. jane.q.smith@examplecompany.com) should also be avoided. Providing the names of individuals involved in the administration of corporate domain names exposes them to an increased risk of social engineering and spear-phishing attacks aimed at the company. Instead, use role-based or department-based names (e.g. hostmaster-technical@example.com, hostmaster-billing@example.com), ideally with several users receiving communications sent to those addresses.

Protect against phishing attacks

Phishing is one of the major attacks used to compromise registrar accounts. Phishing attacks against your DNS administrators should be expected, so a comprehensive phishing defense is imperative. The following suite of anti-phishing techniques can provide effective protection against phishing attacks.

Use generic, role-based or department-based email addresses, such as domain_admin@example.com. Phishing emails which arrive in a role-based account are often easier for administrators to spot.

Include anti-phishing training in your annual security review, and require all DNS administrators to complete the training.

Deploy endpoint security software and enforce security policies on all the devices used by the DNS administrators (as well as everyone in your organization).

Deploy an email filtering service to help prevent some common phishing and malware attacks on your DNS administrators as well as the rest of your organization.

Filter DNS queries to prevent employees from visiting known phishing sites. Tools like Akamai's Secure Internet Access Enterprise provide enterprise security at the DNS level.

There is no "silver bullet" to stop phishing attacks, but adopting the right combination of defenses for your organization will help limit the risk.

Credential updates - change the passwords

Regular password changes are good practice for all online accounts, and domain name registrar accounts are no exception. When performing an audit of your DNS infrastructure, ask everyone with registrar access to rotate their credentials. While your organization may have a comprehensive password policy, it's common to overlook external services like your registrar. External accounts should be subject to your internal password security guidelines and rotation schedule. Passwords for registrar accounts should be long and complex; the use of a password manager can make it easy to generate and store complex passwords in an encrypted, redundant and findable way. Passwords should never be written down or stored in an unencrypted form.

Two-factor authentication (2FA) for registrar accounts

When supported by your registrar, two-factor authentication (2FA) should be required for all accounts. With 2FA, anyone attempting to log in to the registrar will need not only the account password, but a second factor such as a smartphone application or hardware token. 2FA can thwart what might otherwise have been a successful phishing attempt.

When possible, SMS-based 2FA should be avoided. SMS-based 2FA is still better than accounts secured only with passwords, but other methods such as Time-based One-Time Passwords (TOTP), hardware tokens, or push-based 2FA should be preferred. New Digital Identity Guidelines from NIST recommend that SMS as part of 2FA should be deprecated (see NIST Special Publication 800-63B).

If your registrar doesn't support 2FA, request this feature. If they're not receptive to your concerns, consider exploring alternative registrars. In many cases, there are competing domain registrars for the same TLDs, ccTLDs, and gTLDs.

Understand registrar security policies, tools, and processes

There are hundreds of domain name registrars in the world supporting over 1500 TLDs. Some registrars have better security practices than others. Your organization can help guide the industry towards better practices. Learn about your registrar's security practices and policies by reviewing their online documentation. If you're unable to find this information, open a dialogue with your registrar and encourage them to publish this information.

For example, does your registrar provide the support services you need to operate your domain? Does the registrar offer 24 x 7 technical support that allows for troubleshooting during non-business hours? ICANN policy requires your current registrar to notify you of any domain transfer request they receive from the registry, indicating that someone has requested to transfer the domain to a new registrar. Will your registrar send this information only by email, or do you have the option to request it by phone or fax? Does your registrar send notices for all other updates to your domains? ICANN's Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC) works with the ICANN community to provide DNS operational and security guidance. ICANN's SAC 40 Measures to Protect Domain Registration Services Against Exploitation or Misuse and SAC 44 A Registrant's Guide to Protecting Domain Name Registration Accounts are excellent guides for understanding and evaluating a registrar's security practices.

Review the privacy registration options

Many domain name registrars offer Privacy or Proxy Registration Services. These services will hide your personal contact information from the public and replace them with ICANN-complaint contact information. The European Union's (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has changed how information is published in domain registration databases like WHOIS. As a general principle, a role-based approach to the domain registrant information is a way to be GDPR compatible while providing the community with up to date contact information on your domain.

Note: There are some cases where the Proxy or Privacy Registration would impede the verification process required to obtain Organization Validation (OV) and Extended Validation (EV) SSL/TLS Certificates. The process of enabling or disabling Proxy or Privacy Registration can vary by registrar and the timelines should be well understood before subscribing to these services. The delays in turning off privacy registration could result in certificate rotation failures or delays in domain transfers if either are needed. These risks should be considered carefully.

Review and maintain records in your zone

DNS zones contain many hostnames and subdomains, but many DNS administrators may not know which department or business unit is responsible for a given entry. A hostname refers to a record with a type such as A, AAAA, CNAME, TXT, among others. A subdomain is indicated by the presence of NS records, and delegates control over that portion of your zone to a zone on another nameserver.

DNS administrators should know which groups or teams are responsible for each entry in their organization's zone file. If your organization uses an internal ticket tracking system, the information might be stored there, but it may not be easy to access on short notice. Ensuring that you are accurately tracking changes to the zone over time may require updates to your internal processes. Once you can identify the responsible party for each entry in your zone file, you should perform periodic reviews and ensure that records are still needed. Verifying the ownership of each hostname and subdomain, and removing obsolete entries should be part of a normal DNS audit.

Records may be added quickly for new applications, services, or live demos, but those records may linger long after the services in question have been shut down or migrated. As part of your internal product lifecycle, be sure that sufficient attention is paid to decommissioning a service, and that the decommissioning process includes notifying the DNS administrator that a hostname or subdomain is no longer needed.

Pay particular attention to delegated subdomains, since they are designed to cede control of a portion of your zone to another nameserver. Ensure that the NS records are accurate and that they still serve authoritative answers for the subdomain. If your organization delegates a subdomain to a third party DNS provider, it is even more important to check the answers from delegated subdomains frequently, as the outside provider may repurpose those IP addresses without informing you, their customer. If a zone is delegated to a nameserver operated by your organization in a third party cloud provider, be sure to track IP address changes and update the zone delegations accordingly. Public clouds tend to re-use IP addresses rapidly and failure to audit your NS records and associated IP addresses can result in a zone takeover.

Name server and zone file best practices

A DNS audit should include a review of all user accounts on all nameservers under your control including "primary" and "secondary" nameservers. Users with access to a nameserver may be able to edit zone files directly or change the software that runs on the system. Do not rely solely on filesystem permissions or access level protections in your operating system, as exploits or misconfigurations could allow anyone with an account to gain access to the zone file or server configuration utilities. Ensure that access logs are kept to track who logged into the servers; access control and accountability are essential for all parts of your DNS infrastructure. This is of particular importance in a primary-secondary model, where a "primary" name server contains a canonical copy of the zone file, and "secondary" nameservers transfer it from the primary periodically, or on request.

DNS zone file revision control

The management of the zone file itself should also be audited to ensure an appropriate change-management process exists and is enforced. The master copy of the zone file should be stored in a revision control system or other access-controlled storage. When there is a change request, the DNS administrator generates an updated zone file, puts it through a review process, checks it for errors, and only then pushes the new copy to production. In the event that the update results in unexpected behavior, there should be a regularly tested and easy to execute procedure to roll the zone back to the last known good state; a revision control system can help facilitate this rollback. Auditing your DNS infrastructure should also include a regular review of the accounts that have edit access to the revision control system used to maintain the zone file.

Like all of your important data, the zone file and its changelog should be backed up regularly to a secure off-site backup. A trusted backup, combined with revision control, will aid in establishing a "last known good" version of the file for disaster recovery.

In cases where the master copy of your zone file exists on a cloud DNS provider, you should ensure that all accounts with access to edit zone records are subject to the same strong security practices recommended for registrar accounts. Even when using a cloud provider, ensure that you are regularly storing a backup copy of the zone file for use in disaster recovery. Akamai's Edge DNS provides granular access control, two-factor authentication, and the ability to easily download a copy of your zone for backup or audit purposes.

Is your domain locked at the registrar?

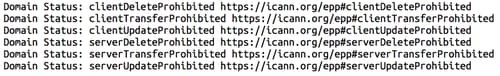

Domain locking is a way to prevent unauthorized changes to a domain's registration. Most domain name registrars allow registrar locks, also known as client locks, for domains they register. Check with your registrar to see if they support this service. If available, ensure your domains are locked. More specifically, it's recommended that at the very least your domains should all have the Client Delete, Client Update and Client Transfer locks set, with the Client Renew lock not set. Some registrars will only present one lock option in their portal which often sets the three recommended locks. This collection of locks will prevent any unauthorized updates to, or transfers of, your domain while also preventing an attacker from deleting the domain registration without first unlocking the domain. By not setting the renew lock, you will still be able to renew domains or take advantage of the auto-renewal feature of your registrar, if offered. Many registrars will not charge you to add registrar locks or client locks to your domains; some will even lock the domains by default without you having to do anything.

In addition to client / registrar locks, some gTLD or ccTLD operators offer server lock, also known as registry lock, services. Server locks add an extra layer of protection to domain updates and can only be added or removed at the request of the registrant through a coordinated, "out-of-band" process with the registry operator, often by phone. Like the client locks, the server locks suggested are Server Delete, Server Update and Server Transfer, with Server Renew not being suggested for the same reason as before. It should be noted that there are Registries/TLD operators that do not offer this service. Making use of the server or registry Lock service often comes at an additional cost and involves added registrant/registrar interaction.

Be aware that adding or removing server / registry locks can result in extended delays (as long as a week) in making changes to a domain, such as updating registration contact information, updating delegation records, domain transfers or domain deletion. For example, when transferring domains between registrars, you would need to unlock the domain before the transfer process can begin.

When making changes to your domain, be sure to use WHOIS to verify that the locks are applied as expected. To query WHOIS information you can either use ICANN's WHOIS page, the whois command through your computer's terminal, or the whois page on your registrar's website. Below you can see an example of how client / registrar locks will appear when applied:

Similarly, when checking WHOIS for both client/registrar and server/registry locks, the following should be returned from your WHOIS query:

Hope for the best; plan for the worst

Domain name registrars have been hacked. DNS administrator accounts have been compromised. Don't wait until it happens to your organization - prepare for it as part of the DNS review and audit exercise. Ask your registrar(s) about their recovery process in the event that your domains are hijacked. They should guide you through the process of preparing appropriate documentation. ICANN's SAC044 recommends collecting the following documentation for the worst case scenario where a domain is hijacked at the registrar:

Copies of domain registration records (ex: timestamped WHOIS lookups, screenshots or exports from the registrar's portal with timestamps)

Billing records, especially ones that show payments have been made

Logs, archives, or financial transactions that associate a domain name with content that you, the rightful registrant, published.

Telephone directories (Yellow Pages), marketing material, etc. that contain advertising that associates you, the registrant, with the domain name

Correspondence to you from registrars and ICANN that mentions the domain name

Legal documents, tax filings, government-issued IDs, business tax notices, etc. that associate you, the registrant, with the domain name

This list comes from the ICANN SSAC, a group of security experts appointed by the ICANN Board. Your organization should leverage their hard-won experience of recovering domains hijacked at the registrar.

What is next?

This guide is just the start of your DNS review and audit exercises. Future articles will dive into DNSSEC, authoritative DNS infrastructure, BGP Hijacking of DNS Resources, secure DNS resolvers, and the range of DNS threats. Stay tuned to Akamai's Blogs and the Akamai Community for future articles.

Additional Reference Guides for a DNS Review and Audit Exercise

These are additional resources and references used in this blog that can help organizations build their review tools.

ICANN's Good Practices for the Registration and Administration of Domain Name Portfolios (Part I)

ICANN's Good Practices for the Registration and Administration of Domain Name Portfolios (Part II)

Good Practices Guide for Deploying DNSSEC By the European Union Agency for Network and Information Security (ENISA)

ICANN's SAC 40 Measures to Protect Domain Registration Services Against Exploitation or Misuse. This is an excellent guide to help organizations walk through the DNS Registration security risk and techniques to mitigate those risk.

ICANN's SAC 44 A Registrant's Guide to Protecting Domain Name Registration Accounts. SAC 44 builds on SAC 40, adding more explicit guidance.

US NIST Secure Domain Name System (DNS) Deployment Guide SP 800-81-2 (2013-09)

Special thanks

Many thanks to our "Akamai DNS Team" and other Akamai colleagues who helped craft and edit this document. This includes Hans Cathcart, Tim April, Jon Reed, Gordon Marx, Bruce Van Nice, Mathias Koerber, Rory Hewitt, James Casey, Barry Greene, and many others who helped.