Phishing Attacks Against Facebook and Google via Google Translate

When it comes to phishing, criminals put a lot of effort into making their attacks look legitimate, while putting pressure on their victims to take action. In today's post, we're going to examine a recent phishing attempt against me personally. This is an interesting attack, as it uses Google Translate, and targets multiple accounts in one go.

Shortly after the New Year holiday, I received an email on my phone notifying me that my Google account had been accessed from a new Windows device. Since I didn't recall logging in via a new device, I decided to examine the email more thoroughly.

I switched over to my laptop and logged into my personal Gmail account. One look at the sender address and my suspicions were confirmed. The email was a complete fake. The interesting thing is, the message looked much more convincing in its condensed state on my mobile device.

Random emails

The message I received on January 7 was pretty basic. It alerted me to the fact that my Google account was accessed from a new device. While the condensed message on my mobile phone appeared legitimate, the full message when viewed on a computer has a number of problems.

First, the supposed security alert itself comes from a Hotmail account. Second, the entire address has nothing to do with Google. By using "facebook_secur", there is a chance a mobile user will assume the message came from Facebook's security team.

Taking advantage of known brand names is a common phishing trick, and it usually works if the victim isn't aware or paying attention. Criminals conducting phishing attacks want to throw people off their game, so they'll use fear, curiosity, or even false authority in order to make the victim take an action first, and question the situation later. When this happens, it is entirely possible - expected, in some cases - that the victim isn't going to pay attention to little details that give the scam away. In my case, the attacker is using a mix of curiosity and fear. Fear that my account is compromised, and curiosity as to who did it.

The attack

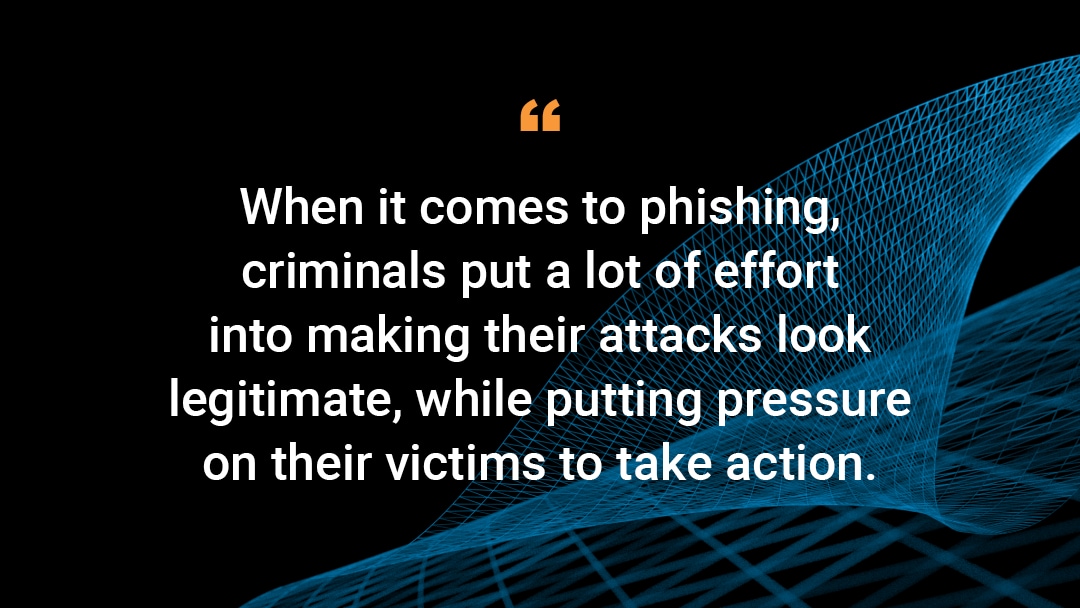

Clicking the embedded "Consult the activity" link brought me to the following page:

Once the link is clicked, the page opens up to the form you see in the image above. This is the landing page. The criminal responsible for this phishing attack is doing something interesting with the landing page, because they're loading the malicious domain through Google Translate.

Using Google Translate does a number of things; it fills the URL (address) bar with lots of random text, but the most important thing visually is that the victim sees a legitimate Google domain. In some cases, this trick will help the criminal bypass endpoint defenses.

However, while this method of obfuscation might enjoy some success on mobile devices (the landing page is a near-perfect clone of Google's older login portal), it fails completely when viewed from a computer.

The entire address used for this attack is in the image below.

Side Note: Customers with Akamai's Secure Internet Access Enterprise are shielded from this URL, as it already exists in our system. The domain, at the time of writing, has been compromised in order to be used for this phishing attack.

If you look at the image, you can clearly see the "mediacity" domain being translated. This should serve as an immediate red flag. For most people, this is where the attack would stop. They'll notice the fake login page and avoid entering their credentials. However, for those who do fall for the scam, the username and password entered will be collected and emailed to the attacker, triggering the second stage of this attack.

A second attack

Once the victim's credentials are sent to the attacker, something interesting happens. A second phishing attack starts. So, not only does the attacker target a victim's Google credentials but they attempt to hit victims twice, by forwarding them to a clone of Facebook's mobile login portal.

Since the Google email and landing page focused on mobile users, it only makes sense that the follow-on attack would do so as well. However, like the Google page, this Facebook landing page also uses an older version of the mobile login form. This suggests that the kit is old, and likely part of a widely circulated collection of kits commonly sold or traded on various underground forums.

The domain hosting the Facebook landing page is different from the domain hosting the Google one, but the two domains are linked via a script being used by the attacker. To give you an idea of what such a script looks like, here is the source code for kits similar to this one.

In this attack, once the Google credentials were recorded and emailed off to the attacker, the script above will format the message accordingly, and send the victim to the Facebook landing page. An example of what one of those emails look like is below on one of our lab systems.

The email records the victim's username and password, as well as other information including IP address and browser type. Some phishing kits will collect more information, such as location, and various levels of PII, which is usually shared or sold for use in credential stuffing attacks or additional phishing attacks.

It isn't every day that you see a phishing attack leverage Google Translate as a means of adding legitimacy and obfuscation on a mobile device. But it's highly uncommon to see such an attack target two brands in the same session. One interesting side note relates to the person driving these attacks, or at the least the author of the Facebook landing page - they linked it to their actual Facebook account, which is where the victim will land should they fall for the scam.

Some phishing attacks are more sophisticated than others. In this case, the attack was easily spotted the moment I checked the message on my computer in addition to seeing it on my mobile device. However, other, more clever attacks fool thousands of people daily, even IT and Security professionals.

The best defense is a good offense. That means taking your time and examining the message fully before taking any actions. Does the from address match what you're expecting? Does the message create a curious sense of urgency, fear, or authority, almost demanding you do something? If so, those are the messages to be suspicious of, and the ones most likely to result in compromised accounts.

Additional research and technical details were provided by Steve Ragan