Kaseya Supply Chain Ransomware Attack

On July 2, 2021, Kaseya disclosed an active attack against customers using its VSA product, and urged all on-premise customers to switch-off Kaseya VSA. Shortly before this alert, users on Reddit started describing ransomware incidents against managed security providers (MSPs), and the common thread among them was on-premise VSA deployments. In the hours to follow, several indicators of compromise (IOCs) were released, and Akamai was able to observe some of that traffic. A patch for the VSA product was released by Kaseya on July 11.

The attack:

The attackers, affiliates of the REvil ransomware group, exploited authentication bypass and arbitrary command execution vulnerabilities (CVE-2021-30116) that enabled them to distribute ransomware encryptors to targeted systems. In order to assist defenders, Kaseya released a number of IOCs related to the ransomware attacks.

Traffic analysis:

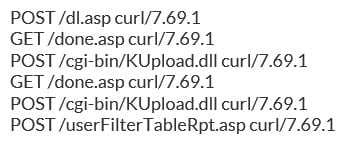

Once IOCs are released, Akamai can leverage our wide view into internet traffic and query petabytes of traffic information to identify key patterns and gain insight into attack sources, distributions, and prevalence. We analyzed HTTPS traffic from the Kaseya attack timeline (July 1 until July 6, 2021) flagging any traffic that was accessing the URLs described in the IOC release.

The goal of our analysis was to determine who was scanning for these URLs, and if the traffic was part of a reconnaissance action (target identification) or actual exploitation attempts. The baseline is that GET/HEAD requests would be reconnaissance and identification, while POST requests would be exploitation. What we found was that essentially all traffic was GET/HEAD-based, meaning it was target scanning traffic, and not part of the exploitation attempts.

However, for the sake of transparency, the low number of POST requests could be an indicator that there were no VSA servers behind Akamai's platform at the time of scanning.

Traffic details:

After queries were complete, Akamai identified 372 HTTP requests in our traffic accounting dataset. Virtually all of them were GET requests (97.85%), followed by HEAD (1.88%) and finally POST (0.27%). As mentioned, the presence of GET/HEAD requests suggests that the traffic was centered on identification and not exploitation. We also identified 88 unique IP addresses. Those details are at the end of this post.

Figure 1: A breakdown of the IOC URL accesses from July 1 until Jul 6, 2021

Figure 1: A breakdown of the IOC URL accesses from July 1 until Jul 6, 2021

We included Jul 1, 2021 in our analysis since this was the day before the public release of details by Kaseya. This shows there could have been some amount of normal, benign traffic. What the data also shows is that many organizations took the warning issued by Kaseya seriously, and shut down, or disabled, the VSA software.

Traffic analysis determined that the most common tool being used was Fuzz Faster U Fool, followed by GoBuster. As the name suggests, Fuzz Faster U Fool - or Ffuf - is a fuzzing tool used for identification. GoBuster is used to brute-force URIs and DNS subdomains. Both are popular tools for bug bounty hunters. In this case, the traffic analysis suggests these tools were being used to search for URLs matching the IOC strings in order to locate vulnerable assets.

Conclusion:

While the scanning and analysis covers a small window of time, it is important to stress that vulnerability scanning and target reconnaissance happen constantly. Attackers are scanning and probing your network on an ongoing basis to look for weaknesses.

Supply chain attacks, like the one experienced by Kaseya's MSP customers and their customers, are a nightmare scenario. This is why it is essential that patches be applied as soon as possible and traffic defenses be monitored and tuned properly.

However, in the case of Kaseya, the attack leveraged a zero-day vulnerability, so there was no patch. In these situations, layered defenses, network segmentation, and disaster recovery plans are critical (including segmented backups). Recovery planning and operations should consider scenarios dealing with supply chain problems, including the complete loss of, or disruption to, managed assets.

Akamai's Threat Research Team is continuing to track traffic associated with the Kaseya incident. Additional blog post updates will be made as needed.

Identified IP addresses:

104.200.29.139

113.173.149.48

117.61.242.70

117.95.232.62

122.178.156.152

123.204.13.110

134.122.114.190

143.110.241.135

143.244.128.87

147.182.172.145

151.244.4.153

154.185.203.234

155.138.162.201

156.217.110.66

159.65.228.100

159.89.177.106

161.35.136.251

161.97.70.207

165.22.205.38

165.22.41.30

167.99.49.144

17.253.80.103

175.101.68.80

175.16.145.28

177.86.198.242

178.128.224.80

178.128.28.156

178.239.173.161

180.94.33.200

183.22.250.36

185.195.19.218

185.65.135.167

188.166.61.213

192.254.65.235

192.40.57.233

193.169.30.10

193.56.252.132

194.195.219.144

194.233.64.67

194.44.192.200

194.5.52.4

194.5.53.98

195.95.131.110

196.64.76.3

199.247.23.87

2.16.186.103

2.16.186.86

2.59.134.200

2.59.135.105

2.92.124.237

20.73.12.15

20.73.12.60

20.74.134.159

202.142.79.81

204.4.182.16

207.244.245.21

222.76.0.230

2604:a880:0400:00d0:0000:0000:1d1b:7001

2a01:04f8:010b:0710:0000:0000:0000:0002

2a01:04f8:1c1c:cc87:0000:0000:0000:0001

2a01:7e00:0000:0000:f03c:92ff:fe12:3d0a

2a0d:5940:0006:01d9:0000:0000:0000:7abe

2a0d:5940:0006:01ea:0000:0000:0000:498d

34.132.164.221

34.132.182.60

34.71.132.48

35.202.142.60

35.232.137.16

35.232.55.163

37.220.119.221

45.124.6.219

45.14.71.9

45.86.201.85

46.19.225.91

50.35.184.96

51.83.140.186

52.15.133.71

52.151.244.28

52.188.217.115

52.20.26.200

52.205.190.252

54.37.72.253

66.23.228.62

76.76.14.36

85.203.46.145

89.39.107.195

91.90.44.22

94.68.117.73