Identifying a DNS Exfiltration Attack That Wasn’t Real — This Time

In late April, 2023, the Akamai ESG SecOps team received a Domain Name System (DNS) exfiltration alert for a customer who had deployed our Secure Internet Access service. After analyzing the customer’s DNS logs, the team was able to identify that the exfiltration activity was associated with the Cobalt Strike tool. We concluded that this domain was either being used by a malicious threat actor or by the customer itself as a part of a security testing exercise.

What is DNS exfiltration?

DNS exfiltration is a technique that attackers use to steal sensitive data from a target system or network by transmitting it through DNS queries and responses. This method is often used in advanced persistent threat (APT) attacks, in which attackers seek to persistently evade detection in the target environment.

Cobalt Strike

One popular tool for carrying out APT attacks is Cobalt Strike, a commercial penetration testing tool that can also be used by threat actors for malicious purposes. Cobalt Strike includes a range of features for stealthy reconnaissance, lateral movement, and data exfiltration, including support for DNS exfiltration.

Running a red vs. blue team event

DNS exfiltration can cause an enterprise significant harm, so the customer was immediately alerted. However, the customer confirmed that a security group within the organization had been running a red vs. blue security teams event in which the red team was using Cobalt Strike.

Thankfully, in this instance there was no immediate risk for the customer. However, this example illustrates that enterprises are concerned about DNS exfiltration and want to ensure that they have effective security tools in place to identify this type of malicious attack.

Analyzing the event

Let’s dig into the methods used by the organization’s “red team” to exfiltrate data through DNS and the steps they took to evade detection.

Between 6 PM on April 24 and 6 PM on April 25, 2023, Secure Internet Access detected DNS exfiltration activity associated with a Zoom-like domain. The communication pattern was identified as being associated with a Cobalt Strike beacon.

There were more than 800,000 DNS queries in the customer’s DNS logs, but after closely observing the fully qualified domain names (FQDN), there were more than 180,000 queries to 28,000 distinct FQDNs. Based on the size of the FQDN queries, we strongly suspected that these were associated with DNS exfiltration activity.

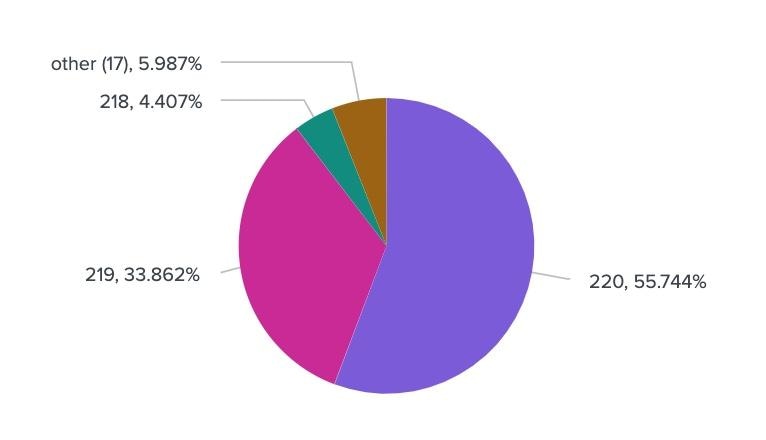

FQDNs with long character counts combined with a high volume of queries in a short period is a common attribute of DNS exfiltration activity (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: FQDN character length distribution

Fig. 1: FQDN character length distribution

FQDN structure

The following is an example of an observed FQDN being used in a DNS query:

d-1ox.<57_character_a-z0-9>.<56_character_a-z0-9>.<56_character_a-z0-9>.<9-10_character_a-z0-9>.primary_domain

d- 1ox[.]3e74f1447fac1785b552d12d250a3d1a56c0335a4af6e37cba0fe86e6[.]13a541b88aefe75b24fd972043f10bd623ba9f6a33345658c8fa5082[.]57b56390b6a309af1d771b242e5f05b849550ae5bdc1b875c21c8334[.]52fab1f01[.]71ef16b6[.]scripts[.]zoom-live[.]net[.]

d- 1ox[.]328eca3d1d7e8d673fd1859de0c4e74a97387ffc7f32fa3c1b3206149[.]7b81b2c405c1645558bb6da0a8aabd5f5bdb3838aa3c5c7dd8b66bd7[.]028e8a7f3231785f8beaf13bdee101438031a3c27d8e0160dfa525b7[.]2842c60b50[.]71ef16b6[.]scripts[.]zoom-live[.]net[.]

d- 1ox[.]392ad8c980917f3ab4c6cd2ec3b8087d37299847bc2106e2505fa9d93[.]1147f41837697988b093fb3c329da246f603cf5cc65c797bbdafadc1[.]1ba5c7639971f63c074b62a8adb51a6769ad38d67afe407da2409641[.]a2fab1f01[.]71ef16b6[.]scripts[.]zoom-live[.]net[.]

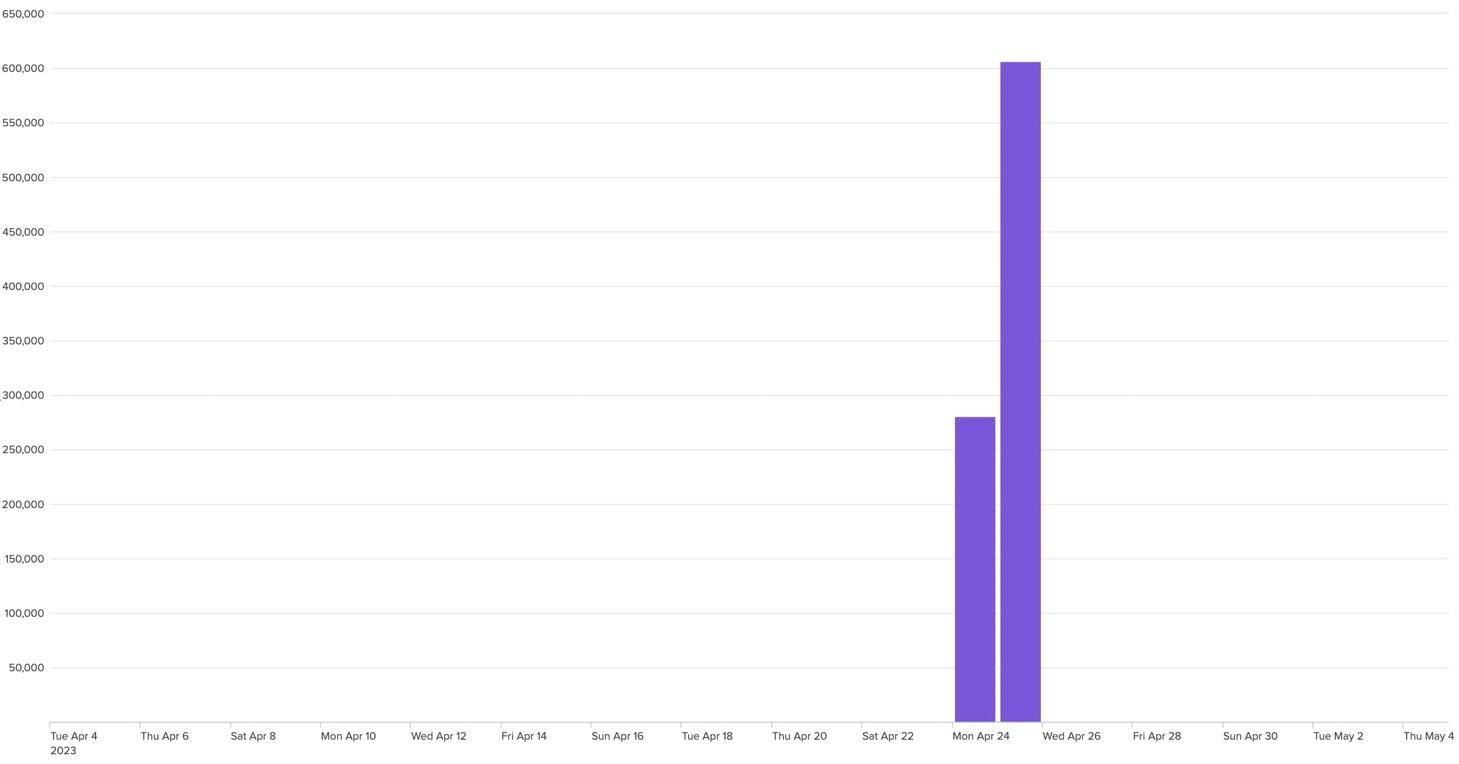

By looking at the global activity in Akamai’s enterprise DNS traffic to zoom-live[.]net, we observed that DNS traffic only occurred during the period of the suspected exfiltration activity (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: DNS activity for zoom-live[.]net

Fig. 2: DNS activity for zoom-live[.]net

Analyzing the size of the suspected exfiltration

Determining the average size of the data exfiltrated in previous DNS exfiltration attacks is difficult, as it can vary widely depending on the specific attack and the data being exfiltrated. However, in general, the amount of data that can be exfiltrated through DNS is limited by the constraints of the protocol and the network environment, as well as the ability of the attacker to evade detection.

In practice, DNS exfiltration attacks are often used to exfiltrate small amounts of data that are critical for the attacker's objectives, such as user login credentials, encryption keys, or other sensitive information that can be used to gain further access to the target system or network. Once armed with that information, attackers can then gain network access and move laterally.

However, there have been some documented cases of DNS exfiltration attacks that have exfiltrated larger amounts of data. For example, in 2017, a group known as APT10 was found to be using DNS exfiltration to steal large amounts of sensitive data from organizations in several regions, including the United States, Europe, and Japan. The group was able to exfiltrate up to 600 MB of data per day using DNS queries and responses.

In this exfiltration detection, if we assume that Base64 encoding was being used, then the maximum size of data that could have been exfiltrated was approximately 22 MB. That’s a small amount of data in a world of terabytes and petabytes, but sufficiently large enough to extract critical data.

Taking a closer look at the associated domain name

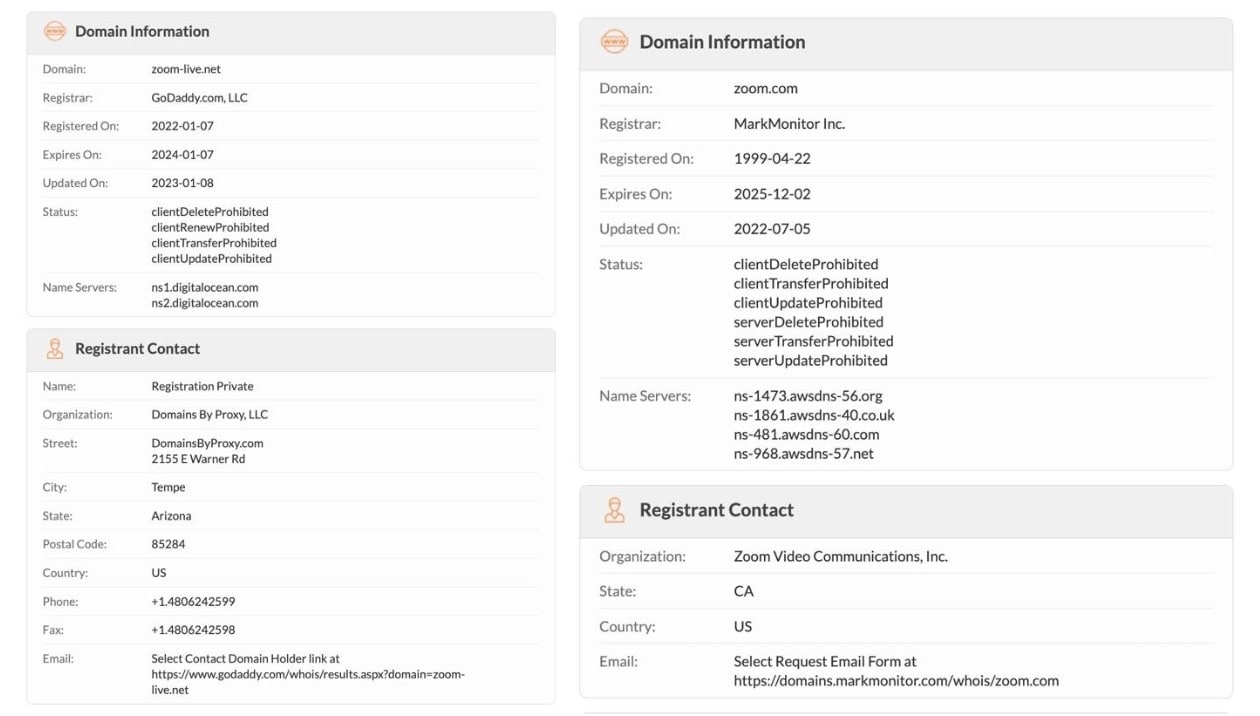

When the FQDN analysis showed the potential for DNS exfiltration, we took a closer look at the associated Zoom domain. All the activity is associated with the zoom-live[.]net domain that was first registered on July 1, 2022, and the registration was updated on January 8, 2023.

As the name suggests, the domain was intended to appear as if it was legitimate and associated with Zoom. But looking at the registration information the domain was not owned by Zoom Inc. (Figure 3).

Fig. 3: The registration information for the associated domain

Fig. 3: The registration information for the associated domain

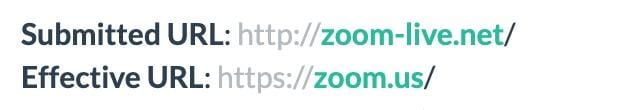

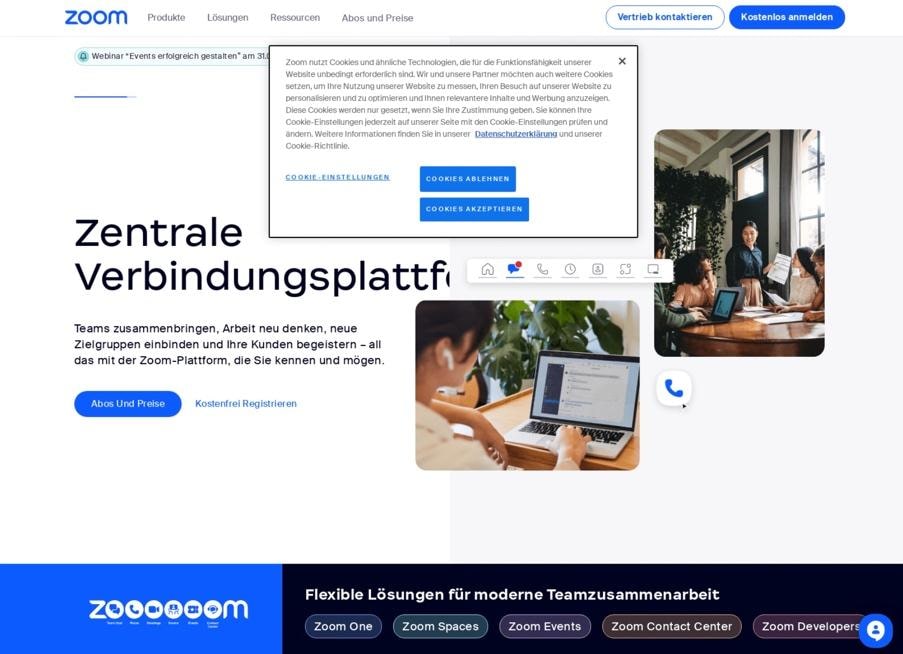

Furthermore, when browsing zoom-live[.]net we were redirected to zoom.us (Figure 4).

Fig. 4: Redirection to zoom.us

Fig. 4: Redirection to zoom.us

Masquerading as legit

This shows how the attackers had obfuscated the queries to masquerade as a legitimate Zoom service.

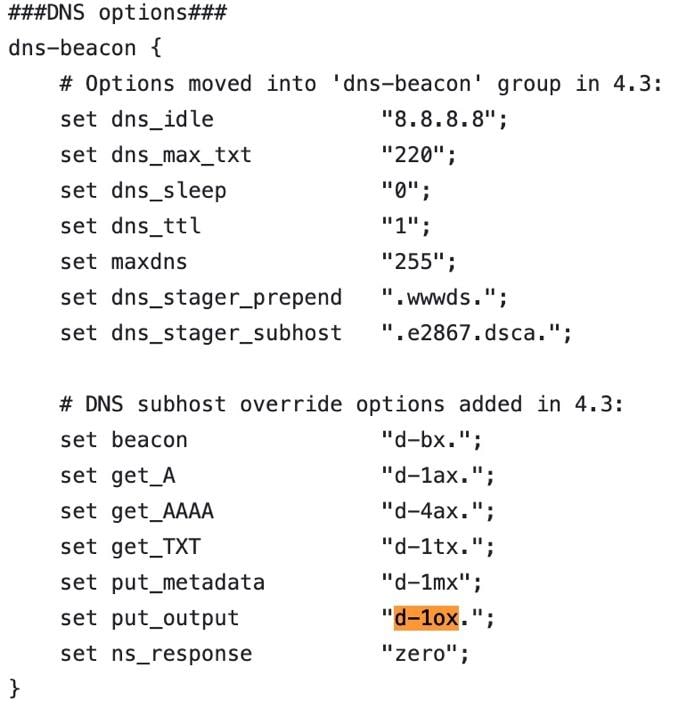

The final confirmation came after searching indicators for “d-1ox,” the string that appears at the start of every FQDN observed in the DNS activity. The returned search results pointed to a GitHub repository that contained a collection of profiles used in different projects using Cobalt Strike (Figure 5).

After combining all the indications, DNS query activity pattern, domain information, and the Cobalt Strike connection, we concluded that this domain was either being used by a malicious threat actor or being used as a part of a security testing exercise.

Fig. 5: GitHub repository containing profiles used in Cobalt Strike attacks

Fig. 5: GitHub repository containing profiles used in Cobalt Strike attacks

Alert plus analysis

Although the DNS exfiltration detection was related to an emulated red vs. blue security teams event, the customer seemed grateful that Akamai Secure Internet Access had detected the activity and that the ESG SecOps team had provided a detailed analysis of the event.

This convinced them that they had in place effective security controls and that Akamai would not only send an alert, but also provide an analysis to show the incident’s context to aid in their investigations. In an era when security talent is often in short supply, and security teams have a lot to deal with, receiving more than just an alert is hugely beneficial in reducing resolution time.

Learn more

Find out more about Akamai’s solution for identifying and analyzing DNS exfiltration.